Paris Fashion Week 2025:

Sustainable Fashion or Glamour?

.

AYA | JUNE 27, 2025

READING TIME: 7 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

AYA | JUNE 27, 2025

READING TIME: 7 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

Paris Fashion Week (PFW) remains the crown jewel of the fashion world—but behind the spectacle lies a heavy environmental toll. In a typical year, the “Big Four” fashion weeks—New York, London, Milan, and Paris—collectively produce around 241,000 tonnes of CO₂ emissions [1], with New York leading the pack and Paris close behind [2].

In this blog, we take a closer look at the true footprint of PFW 2025: from the carbon cost of global travel and high-flying luxury to digital alternatives and ethical gray areas. We'll explore the comprehensive impact of the Fashion Weeks and the mounting pressure on luxury brands to reinvent themselves sustainably.

Carbon Footprint: Travel, Shows & Infrastructure

A huge share of Fashion Week’s emissions comes from transport. Industry studies estimate that flights alone for designers, buyers, journalists and celebrities generate on the order of 147,000 tonnes of CO₂ per year across all major fashion weeks [2]. (For perspective, that’s equivalent to 10,000 round-trip flights New York–Paris.) Much of this is long-haul air travel, often in premium class. In fact, flying business-class emits roughly 3× more CO₂ per person than economy (and first class about 9× more) [3], because those seats take up more space and carry heavier furnishings.

Beyond the runway flights, Fashion Week also relies on massive production infrastructure: energy-intensive lighting rigs and elaborate stage sets. While precise figures are scarce, experts note that even lighting and sound for a single 15‑minute show can burn thousands of kilowatt-hours. Hotels and ground transport add another layer: one estimate puts accommodation and local travel for the week at 78,000 tonnes CO₂ (for hotels and taxis) [2]. In short, each Paris Fashion Week show—even a modest one—can generate tens of thousands of tonnes of CO₂ once you factor in flights, electricity, heating and support services [2].

Picture by Dennis Zhang.

Runway Shows: Single-Use & Invitations

Beyond carbon emissions, Fashion Week generates enormous streams of waste. Each show often involves custom-built sets, props, and decorations designed to last only a few minutes—paper sculptures, theatrical backdrops, extravagant installations—all destined for the landfill or recycling immediately after the show. Industry insiders often describe a typical post-show scene as “a dumpster full of plastic water bottles, printed press notes, invitations, flowers, and decor” [4].

On top of that, there's the massive waste of water, electricity, and raw materials during the production of Fashion Week collections. Some reports suggest that producing a single runway show can consume more resources than six months of the collection’s actual wear and use [5].

Textile Waste in Fashion Weeks

Unsold Clothing and Limited Editions

Many of the pieces created for runway shows are one-of-a-kind or part of limited samples—and most never make it to stores. Industry estimates suggest that 15–30% of garments produced are never sold, ending up destroyed or stored indefinitely [6,7]. That’s a massive loss of resources before garments even reach consumers. At events like Paris Fashion Week, where hundreds of exclusive looks are shown just once, the scale of this waste is even more pronounced.

Production Waste

Behind every couture show is a surprising amount of textile waste. On average, 15–20% of fabric is lost during the cutting and production process due to offcuts, alterations, and rejected pieces [8]. In haute couture—where garments are complex and precision-made—this adds up fast, often amounting to hundreds of meters of discarded fabric per collection.

Oil-based and Synthetic Fibers

Roughly 65–70% of textiles used on the runway are synthetic—think polyester, nylon, and acrylic [9]. These oil-based fibers are non-biodegradable and can take 200 to 400 years to break down [10,11]. Their environmental impact doesn’t stop there: they require significant water and energy to produce, and every wash releases microplastics into the environment.

Paris Fashion Week S/S 2024. Picture by Miu Miu.

Fashion Week Format: From Spectacle to Intimacy

As sustainability pressures mount, recent Fashion Weeks—particularly in Paris—have seen a noticeable shift from large-scale theatrics to more intimate, stripped-back runway presentations. Balenciaga, for instance, narrowed its runway to the width of a standard office chair, with guests seated in a single row right next to the models, highlighting what designer Demna called “proximity to the clothes” [12].

Less drama, more consequences?

While smaller shows may cut emissions—fewer people flying in, less elaborate sets, lower energy use—they also unintentionally open the door wider for fast fashion. By making runway looks feel more "everyday" and wearable, designers are creating styles that are easier to replicate at scale. Fashion Week’s shift toward realism still “creates the desire” that fuels mass-market copies and overconsumption [13].

Do haute couture and fast fashion both benefit?

Interestingly, this more accessible approach to fashion can benefit both high-end and fast fashion brands—though in very different ways.

A 2024 study published by the Journal of Marketing Research [14] found that fast fashion “copycats” produce a dual effect:

- On one hand, they can cannibalize luxury sales by offering similar designs at a fraction of the price [15].

- On the other, they can expand the market by increasing brand awareness and demand for the original styles [15].

On the other, they can expand the market by increasing brand awareness and demand for the original styles [15]. The effect depends largely on the level of similarity:

- If fast fashion copies are too close to the original, they can erode exclusivity and dilute the luxury brand.

- But when they’re similar enough to evoke a vibe, without being identical, they fuel aspirational desire—encouraging consumers to seek out the real thing.

Haute couture and top-tier ready-to-wear aren’t aimed at your local mall – they exist to spark trends and give brands a “halo effect” . A sumptuous Paris catwalk can transform a simple garment into an aspirational symbol. For instance, a plain logo tee that might retail for $500 can shoot to the top of fashion wishlists simply by being featured on a runway or worn by celebrities [13,16]. That cachet trickles down: within weeks fast-fashion chains have copied the look in cheap polyester.

Ultimately, this shift to “real clothes” on the runway may reduce emissions and waste—but it also speeds up trend cycles. Fast fashion retailers benefit from the immediacy and relatability of these designs, while luxury brands gain cultural capital but must work harder to preserve their distinctiveness in a sea of lookalikes.

Models walk the runway during the Chanel Womenswear Spring/Summer 2021 show as part of Paris Fashion Week. Picture by Pascal Le Segretain.

Sustainable Alternatives & Industry Pressure

The rising critique around Fashion Week’s environmental footprint is driving change. In recent years, both innovation and public pressure have nudged the industry toward more sustainable practices.

A few leaders are showing that sustainability and style can coexist. Stella McCartney, for example, has long championed cruelty-free and recycled materials, often bypassing traditional runway shows in favor of museum-style exhibits or smaller, low-impact events. Her collections feature up to 90% sustainable fabrics, including grape leather and recycled cashmere—proof that luxury doesn’t have to come at the planet’s expense [17]. Similarly, Collina Strada primarily uses deadstock and recycled textiles [5].

Even event organizers are stepping up: Copenhagen Fashion Week now requires all participating designers to meet strict environmental criteria, including using at least 50% certified or recycled materials per collection [18]. In the UK, the British Fashion Council has banned exotic skins at London Fashion Week starting in 2025—a symbolic move, given that Paris, Milan, and New York have yet to follow suit [18].

Still, while these advances are promising, they don’t address fashion’s biggest blind spot: mass production. Regardless of how sustainable a material is, if clothes are being produced at excessive volumes, they will continue to strain the planet. Even recycled fabrics have a footprint. For example, producing recycled polyester still emits up to 50% of the carbon emissions of virgin polyester and continues to shed microplastics when washed [19]. Moreover, less than 1% of all clothing worldwide is actually recycled back into new garments, highlighting the limits of circularity in practice [19,20].

On the other hand, designers are experimenting with upcycling on the runway: Gabriela Hearst famously reconstructed vintage mink coats into new knit patterns for AW25, blending haute couture with reuse [21]. Even fast-fashion brands are under pressure to replace petroleum-derived synthetics with biodegradable or recycled fibers.

In other words, eco-friendly materials are a step forward—but without tackling the sheer scale of production, consumption and afterlife, Fashion Week’s sustainability efforts risk becoming another form of greenwashing.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Extinction Rebellion protestors at London Fashion Week Picture by Niklas Halle'n.

Future Directions: Innovation & Conclusion

What might Fashion Week become next? Analysts suggest major structural reforms. One idea is to merge or reduce shows to curb travel. The Carbon Trust and consultants propose combining men’s and women’s collections in single events, co‑locating seasons, or even choosing a single host city per season (rather than staging four separate weeks) [2]. In this “Olympic model,” Paris might rotate the spotlight with other capitals, or showcase only the most essential presentations. Hybrid formats are also in play: as digital streaming cuts costs and carbon (though live engagement still lags), some envision “showrooms” and augmented reality runways supplementing physical events [2].

Paris Fashion Week epitomizes couture’s beauty and excess—but the numbers tell an uncompromising story. The opulence of the runway comes with undeniable carbon and ethical costs. Private jets, overnight stays, and pyrotechnic sets all add up to a climate footprint that no amount of chic can disguise. The big question: can brands balance prestige with the planet? Many say yes, if luxury is redefined.

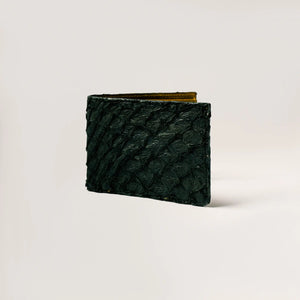

At AYA, for example, we believe fashion can aspire without expiring: every AYA garment is made in a traceable, single-origin supply chain (all in Peru) to keep miles—and emissions—low. We use only biodegradable and certified fibers (100% organic pima cotton) so that at the end of life the cloth returns safely to earth. In our view, true elegance is a transparent journey from field to fabric, not a carbon-churning spectacle.

The real showdown is yet to come: as Fashion Week 2025 wraps up, will carbon counting become as paramount as trend forecasting? Can luxury houses “show” responsibility as well as showmanship?

AYA Collection: 100% organic pima cotton, plastic-free and natural dyes.

Glossarykeywords

CO₂ emissions:

The amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. In this context, it's the greenhouse gases produced by travel, electricity, and heating during Fashion Weeks.

Mass-market knockoffs:

Low-cost replicas of luxury garments created by fast-fashion brands at scale.

Biodegradable:

Materials that decompose naturally without harming the environment (e.g., natural dyes, organic cotton). Essential for reducing textile waste.

Carbon Footprint:

The total greenhouse gas emissions caused by an individual, event, organization, or product lifecycle.

Long-haul air travel:

Flights covering long distances (e.g., New York–Paris). Business and first-class seats emit significantly more CO₂ than economy class.

Single-use sets:

Custom stage designs built only for one show and then discarded.

Deadstock:

Excess or leftover fabrics from past seasons that are reused instead of being discarded.

Oil-based fibers:

Synthetic textiles like polyester, nylon, and acrylic, derived from petroleum and non-biodegradable over centuries.

Microplastics:

Tiny plastic particles shed from synthetic clothing when washed, polluting waterways and oceans.

Haute couture:

High-end, custom-fitted fashion made in limited quantities—epitomizing luxury and exclusivity.

Fast fashion:

Mass-produced, low-cost clothing rapidly produced to mirror runway and celebrity trends.

Copycat effect:

When fast fashion replicates runway designs, which can both dilute luxury brands and increase their visibility.

Greenwashing:

The practice of marketing products or events as eco-friendly without making substantial sustainable changes.

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Authors & Researchers

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

References:

[1] Global Measure. Fashion Week and sustainability [Internet].Global Measure; 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://globalmeasure.org/fashion-week-and-sustainability/

[2] NSS Magazine. Y‑project for sale [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.nssmag.com/en/fashion/38340/y-project-for-sale

[3] Climate Action Accelerator. Economy class tickets only [Internet]. Geneva: Climate Action Accelerator; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://climateactionaccelerator.org/solutions/economy_class_tickets_only/

[4] Vogue. What’s the Carbon Footprint of a Fashion Show? No One Really Knows [Internet]. New York: Vogue; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.vogue.com/article/fashion-week-sustainability-carbon-footprint-runway-show

[5] Sustainable Fashion by Raya. Fashion Week Is Not Sustainable [Internet].Sustainable Fashion by Raya; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://sustainablefashionbyraya.com/fashion-week-is-not-sustainable

[6] Public Interest Research Group (PIRG). What’s the problem with fast fashion? [Internet]. PIRG; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://pirg.org/articles/whats-the-problem-with-fast-fashion/

[7] Fabric of Change. The hidden waste of fast fashion [Internet]. Fabric of Change; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.fabricofchange.ie/articles/the-hidden-waste-of-fast-fashion

[8] Sawhney MK. Zero Waste Fashion: Exploring Zero-Waste Pattern Cutting to Eliminate Fabric Waste in the Garment Manufacturing Industry. Latest Trends in Textile and Fashion Designing. 2023 Sep 11;6. doi:10.32474/LTTFD.2023.06.000226.

[9] United Nations Environment Programme. Fashion’s tiny hidden secret. UNEP; 2019 Mar 13.; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/fashions-tiny-hidden-secret

[10] Royer SJ, Wiggin K, Kogler M, Deheyn DD. Degradation of synthetic and wood-based cellulose fabrics in the marine environment: Comparative assessment of field, aquarium, and bioreactor experiments. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Oct 15;791:148060. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148060.

[11] Sustainability Directory. Textile Degradation. Sustainability Directory; 2025 May 21. Available from: https://fashion.sustainability-directory.com/term/textile-degradation

[12] Bramley EV. Skin in the game: mink coat at ethical fashion show fuels sustainability debate. The Guardian. 2025 Mar 10. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2025/mar/10/skin-in-the-game-mink-coat-at-ethical-fashion-show-fuels-sustainability-debate

[13] Farra E. What’s the carbon footprint of a fashion show? No one really knows. Vogue. 2019 Sep 3. Available from: https://www.vogue.com/article/fashion-week-sustainability-carbon-footprint-runway-show

[14] Shi ZJ, Liu X, Lee D, Srinivasan K. How Do Fast Fashion Copycats Affect the Popularity of Premium Brands? Evidence from Social Media [Internet]. Boston University Questrom School of Business Research Paper No. 4246136; 2022 Oct 19 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4246136

[15] Zerbo J. How Fast-Fashion Copycats Hurt—and Help—High-End Fashion Brands. AMA. 2024 Apr 3. Available from: https://www.ama.org/2024/04/03/how-fast-fashion-copycats-hurt-and-help-high-end-fashion-brands/

[16] Ledger FE. From runway to rack: how fast fashion hacked the catwalk. Whering. 2024 Feb 20. Available from: https://whering.co.uk/thoughts/runway-to-rack

[17] Time.com. Stella McCartney Is Changing Fashion From Within. TIME. 2023 Nov 16. Available from: https://time.com/6302562/stella-mccartney-sustainability-interview-lvmh/

[18] Greenfield P. ‘Ridiculous’ ban on exotic animal skins at London fashion week criticised by experts. The Guardian. 2024 Dec 18. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/dec/18/ban-on-exotic-skins-london-fashion-week

[19] Ro C. Can fashion ever be sustainable? [Internet]. BBC Future. 2020 Mar 10 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200310-sustainable-fashion-how-to-buy-clothes-good-for-the-climate

[20] Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future [Internet]. 2017 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy

[21] Moore B. Gabriela Hearst Fall 2025: The Luxury of Doing the Right Thing. Runway, Paris 2025 Fall Ready-to-Wear. 2025 Mar 10. Available from: https://wwd.com/runway/fall-2025/paris/gabriela-hearst/review/

Glossarykeywords

CO₂ emissions:

The amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. In this context, it's the greenhouse gases produced by travel, electricity, and heating during Fashion Weeks.

Mass-market knockoffs:

Low-cost replicas of luxury garments created by fast-fashion brands at scale.

Biodegradable:

Materials that decompose naturally without harming the environment (e.g., natural dyes, organic cotton). Essential for reducing textile waste.

Carbon Footprint:

The total greenhouse gas emissions caused by an individual, event, organization, or product lifecycle.

Long-haul air travel:

Flights covering long distances (e.g., New York–Paris). Business and first-class seats emit significantly more CO₂ than economy class.

Single-use sets:

Custom stage designs built only for one show and then discarded.

Deadstock:

Excess or leftover fabrics from past seasons that are reused instead of being discarded.

Oil-based fibers:

Synthetic textiles like polyester, nylon, and acrylic, derived from petroleum and non-biodegradable over centuries.

Microplastics:

Tiny plastic particles shed from synthetic clothing when washed, polluting waterways and oceans.

Haute couture:

High-end, custom-fitted fashion made in limited quantities—epitomizing luxury and exclusivity.

Fast fashion:

Mass-produced, low-cost clothing rapidly produced to mirror runway and celebrity trends.

Copycat effect:

When fast fashion replicates runway designs, which can both dilute luxury brands and increase their visibility.

Greenwashing:

The practice of marketing products or events as eco-friendly without making substantial sustainable changes.

Glossarykeywords

Bamboo:

The term "bamboo fabric" generally refers to a variety of textiles made from the bamboo plant. Most bamboo fabric produced worldwide is bamboo viscose, which is economical to produce, although it has environmental drawbacks and poses occupational hazards.

Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs):

They are rod-shaped nanoparticles derived from cellulose. They are biodegradable and renewable materials used in various fields, such as construction, medicine, and crude oil separation.

Circularity in the Textile Value Chain:

It seeks to design durable, recyclable, and long-lasting textiles. The goal is to create a closed-loop system where products are reused and reincorporated into production.

Cotton:

A soft white fibrous substance that surrounds the seeds of a tropical and subtropical plant and is used as textile fiber and thread for sewing.

Fertilizers:

These are nutrient-rich substances used to improve soil characteristics for better crop development. They may contain chemical additives, although there are new developments in the use of organic substances in their production.

Jute:

It is a fiber derived from the jute plant. This plant is composed of long, soft, and lustrous plant fibers that can be spun into thick, strong threads. These fibers are often used to make burlap, a thick, inexpensive material used for bags, sacks, and other industrial purposes. However, jute is a more refined version of burlap, with a softer texture and a more polished appearance.

Hemp:

Industrial hemp is used to make clothing fibers. It is the product of cultivating one of the subspecies of the hemp plant for industrial purposes.

Linen:

It is a plant fiber that comes from the plant of the same name. It is very durable and absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Thanks to these properties, it is comfortable to wear in warm climates and is valued for making clothing.

Organic Cotton:

It is grown with natural seeds, sustainable irrigation methods, and no pesticides or other harmful chemicals are used in its cultivation. As a result, organic cotton is presented as a healthier alternative for the skin.

Pesticides:

It is a substance used to control, eliminate, repel, or prevent pests. Industry uses chemical pesticides for economic reasons.

Subsidy:

It can be defined as any government assistance or incentive, in cash or kind, towards private sectors - producers or consumers - for which the Government does not receive equivalent compensation in return.

The International Day of Zero Waste:

It is celebrated annually on March 30. The day's goal is to promote sustainable consumption and production and raise awareness about zero-waste initiatives.

UNEP:

The United Nations Environment Programme is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental problems within the United Nations system.

Water-Intensive Practices:

These are activities that consume large amounts of water. These practices can have significant environmental impacts, especially in water-scarce regions.

World Water Day:

It is an international celebration of awareness in the care and preservation of water that has been celebrated annually on March 22 since 1993.

Glossarykeywords

Artisan:

A skilled craftsperson who makes products by hand, often using traditional methods passed down through generations.

Dignity:

The state of being worthy of respect. In fashion, it refers to treating workers as valuable human beings, not disposable labor.

Exploitation:

The unfair treatment or use of someone for personal gain, especially by paying them unfairly or subjecting them to unsafe conditions.

Fair trade:

A global movement and certification system that promotes ethical, transparent, and sustainable business practices for producers and workers.

Living wage:

A salary that covers the basic needs of a worker and their family, including housing, food, education, and healthcare.

Overproduction:

The excessive manufacture of goods beyond demand, common in fast fashion, leading to waste and environmental damage.

Transparency:

The practice of openly sharing information about sourcing, production, and labor conditions to allow accountability and informed decisions.

Slow fashion:

A movement that promotes mindful, sustainable, and ethical production and consumption of clothing, focusing on quality over quantity.

Glossarykeywords

Air Dye:

A waterless dyeing technology that uses air to apply color to textiles, eliminating wastewater and reducing chemical use.

Automation in Textile Production:

The use of AI, robotics, and machine learning to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and lower production costs in the fashion industry.

Carbon Emissions:

Greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), released by industrial processes, transportation, and manufacturing, contributing to climate change.

Circular Economy:

A production and consumption model that minimizes waste and maximizes resource efficiency by designing products for durability, reuse, repair, and recycling.

CO₂ Dyeing (DyeCoo):

A sustainable dyeing technology that uses pressurized carbon dioxide instead of water, significantly reducing water waste and pollution.

Ethical Fashion:

Clothing produced in a way that considers the welfare of workers, animals, and the environment, ensuring fair wages and responsible sourcing.

Fast Fashion:

A mass production model that delivers low-cost, trend-based clothing at high speed, often leading to waste, environmental pollution, and unethical labor practices.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

A leading certification for organic textiles that ensures responsible farming practices, sustainable processing, and fair labor conditions.

Greenwashing:

A misleading marketing strategy used by companies to appear more environmentally friendly than they actually are, often exaggerating sustainability claims.

Nanobubble Technology:

A textile treatment method that applies chemicals and dyes using microscopic bubbles, reducing water and chemical usage.

Natural Dyes:

Dyes derived from plants, minerals, or insects that are biodegradable and free from toxic chemicals, unlike synthetic dyes.

Ozone Washing:

A low-impact textile treatment that uses ozone gas instead of chemicals and water to bleach or fade denim, reducing pollution and water consumption.

Proximity Manufacturing:

The practice of producing garments close to consumer markets, reducing transportation-related carbon emissions and promoting local economies.

Recycled Polyester (rPET):

Polyester made from post-consumer plastic waste (e.g., bottles), reducing dependence on virgin petroleum-based fibers.

Slow Fashion:

A movement opposing fast fashion, focusing on sustainable, high-quality, and ethically made clothing that lasts longer.

Sustainable Fashion:

Clothing designed and manufactured with minimal environmental and social impact, using eco-friendly materials and ethical labor practices.

Upcycling:

The creative reuse of materials or textiles to create new products of equal or higher value, reducing waste without breaking down fibers.

Wastewater Recycling:

The treatment and reuse of water in textile production, minimizing freshwater consumption and reducing pollution.

Zero-Waste Design:

A fashion design approach that maximizes fabric efficiency, ensuring that no textile scraps go to waste during the cutting and sewing process.

References:

[1] Global Measure. Fashion Week and sustainability [Internet].Global Measure; 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://globalmeasure.org/fashion-week-and-sustainability/

[2] NSS Magazine. Y‑project for sale [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.nssmag.com/en/fashion/38340/y-project-for-sale

[3] Climate Action Accelerator. Economy class tickets only [Internet]. Geneva: Climate Action Accelerator; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://climateactionaccelerator.org/solutions/economy_class_tickets_only/

[4] Vogue. What’s the Carbon Footprint of a Fashion Show? No One Really Knows [Internet]. New York: Vogue; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.vogue.com/article/fashion-week-sustainability-carbon-footprint-runway-show

[5] Sustainable Fashion by Raya. Fashion Week Is Not Sustainable [Internet].Sustainable Fashion by Raya; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://sustainablefashionbyraya.com/fashion-week-is-not-sustainable

[6] Public Interest Research Group (PIRG). What’s the problem with fast fashion? [Internet]. PIRG; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://pirg.org/articles/whats-the-problem-with-fast-fashion/

[7] Fabric of Change. The hidden waste of fast fashion [Internet]. Fabric of Change; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.fabricofchange.ie/articles/the-hidden-waste-of-fast-fashion

[8] Sawhney MK. Zero Waste Fashion: Exploring Zero-Waste Pattern Cutting to Eliminate Fabric Waste in the Garment Manufacturing Industry. Latest Trends in Textile and Fashion Designing. 2023 Sep 11;6. doi:10.32474/LTTFD.2023.06.000226.

[9] United Nations Environment Programme. Fashion’s tiny hidden secret. UNEP; 2019 Mar 13.; [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/fashions-tiny-hidden-secret

[10] Royer SJ, Wiggin K, Kogler M, Deheyn DD. Degradation of synthetic and wood-based cellulose fabrics in the marine environment: Comparative assessment of field, aquarium, and bioreactor experiments. Sci Total Environ. 2021 Oct 15;791:148060. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148060.

[11] Sustainability Directory. Textile Degradation. Sustainability Directory; 2025 May 21. Available from: https://fashion.sustainability-directory.com/term/textile-degradation

[12] Bramley EV. Skin in the game: mink coat at ethical fashion show fuels sustainability debate. The Guardian. 2025 Mar 10. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2025/mar/10/skin-in-the-game-mink-coat-at-ethical-fashion-show-fuels-sustainability-debate

[13] Farra E. What’s the carbon footprint of a fashion show? No one really knows. Vogue. 2019 Sep 3. Available from: https://www.vogue.com/article/fashion-week-sustainability-carbon-footprint-runway-show

[14] Shi ZJ, Liu X, Lee D, Srinivasan K. How Do Fast Fashion Copycats Affect the Popularity of Premium Brands? Evidence from Social Media [Internet]. Boston University Questrom School of Business Research Paper No. 4246136; 2022 Oct 19 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4246136

[15] Zerbo J. How Fast-Fashion Copycats Hurt—and Help—High-End Fashion Brands. AMA. 2024 Apr 3. Available from: https://www.ama.org/2024/04/03/how-fast-fashion-copycats-hurt-and-help-high-end-fashion-brands/

[16] Ledger FE. From runway to rack: how fast fashion hacked the catwalk. Whering. 2024 Feb 20. Available from: https://whering.co.uk/thoughts/runway-to-rack

[17] Time.com. Stella McCartney Is Changing Fashion From Within. TIME. 2023 Nov 16. Available from: https://time.com/6302562/stella-mccartney-sustainability-interview-lvmh/

[18] Greenfield P. ‘Ridiculous’ ban on exotic animal skins at London fashion week criticised by experts. The Guardian. 2024 Dec 18. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/dec/18/ban-on-exotic-skins-london-fashion-week

[19] Ro C. Can fashion ever be sustainable? [Internet]. BBC Future. 2020 Mar 10 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200310-sustainable-fashion-how-to-buy-clothes-good-for-the-climate

[20] Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future [Internet]. 2017 Nov 28 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy

[21] Moore B. Gabriela Hearst Fall 2025: The Luxury of Doing the Right Thing. Runway, Paris 2025 Fall Ready-to-Wear. 2025 Mar 10. Available from: https://wwd.com/runway/fall-2025/paris/gabriela-hearst/review/

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

EU Green Claims Reversal: What This Means for Greenwashing

The EU's Green Claims Directive is gone. Understand the real impact of greenwashing on your choices and learn how to identify brands that are truly transparent.

France's new law

France has taken a bold step against ultra-fast fashion, targeting brands like Shein with new environmental laws. Discover what this means for sustainability and the future of clothing.

Plastic-Free July: Say No to Single-Use Plastic and Synthetic Clothing

Discover the hidden microplastic footprint of synthetic clothing and fast fashion. Explore the benefits of organic cotton for a truly sustainable wardrobe.

Organic Cotton vs. Conventional Cotton: Environmental, Health & Social Impact

Discover how organic cotton drastically reduces water use, pesticide exposure and environmental harm, while producing longer-lasting, toxin-free garments.