World Environment Day 2025:

Embracing Sustainable Fashion Practices

.

AYA | JUNE 5, 2025

READING TIME: 5 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

AYA | JUNE 5, 2025

READING TIME: 5 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

As we commemorate World Environment Day, it's imperative to reflect on the environmental impact of our choices, particularly in the fashion industry. The fashion sector is a significant contributor to global pollution, but by adopting sustainable practices, we can mitigate its adverse effects.

The Role of Organic Agriculture in Fashion

Organic farming plays a pivotal role in reducing the environmental footprint of textile production. Unlike conventional agriculture, which relies heavily on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, organic methods promote soil health, biodiversity, and water safety by working with, rather than against, natural systems [1].

This approach not only protects surrounding ecosystems, but also safeguards the well-being of farmers, reducing their exposure to toxic substances that are common in industrial agriculture. Research shows that organic systems reduce pesticide use by up to 97% and cut nitrate leaching by nearly 50%, helping to prevent contamination of waterways and groundwater [2,3].

Moreover, organic farming enhances soil structure and fertility, increasing organic carbon content by around 26% compared to conventional systems [2]. The presence of soil biodiversity—especially earthworms—is also significantly higher, with studies showing 30–40% greater abundance in organically managed soils [2,4]. This rise in biological activity improves water retention, nutrient cycling, and long-term productivity [2].

In the context of textile fibers like organic cotton or regenerative plant-based materials, these benefits translate into clothing that begins its life cycle with care—for people, for the planet, and for the future of farming.

Natural and GOTS-Certified Dyes: A Healthier Alternative

The dyeing process in textile manufacturing is one of the most chemically intensive phases—often overlooked, yet deeply impactful. Today, the industry uses more than 3,600 synthetic dyes and over 8,000 chemical substances across processes like dyeing, fixing, and printing [5]. Many of these compounds are derived from petroleum, and up to 40% contain chlorinated elements, which have been linked to carcinogenic effects and persistent environmental harm [5,6].

These chemicals can leach into waterways, affect aquatic life, and expose workers and nearby communities to long-term health risks. Without adequate regulation or wastewater treatment, the environmental toll is profound [5,6].

In contrast, natural dyes, sourced from plants, minerals, or insects, offer a biodegradable and non-toxic alternative. They reconnect color-making with traditional knowledge and reduce dependency on fossil-based chemicals [7]. To ensure both safety and accountability, certifications like the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) go a step further: even when synthetic dyes are used, they must comply with strict criteria that ban harmful substances, mandate wastewater treatment, and uphold fair labor conditions [8].

Importance of Traceability and Transparency

In today's fashion landscape, transparency is no longer optional—it’s expected. Consumers increasingly want to know where their garments come from, who made them, and how they were produced. In fact, recent data shows that 54% of consumers associate traceability with the fashion industry, and 57% link it directly to sustainability [9].

Traceability empowers brands to monitor every stage of the supply chain, from raw material sourcing to final production. It allows for the verification of claims—like whether cotton is truly organic, or whether wool was sourced from farms practicing animal welfare [9]. This level of visibility ensures ethical practices, better quality control, and real-time accountability [9,10].

More than a marketing tool, traceability is a key mechanism for driving systemic change. It fosters trust between brands and consumers, but also puts pressure on the industry to improve labor conditions, reduce environmental harm, and prioritize fairness. It is particularly vital for protecting workers’ rights and promoting social justice across the textile sector [9,10].

At the same time, the lack of transparent data—especially on waste, emissions, and chemical use—continues to block the adoption of circular models [11]. Without understanding what goes into and comes out of each step, truly regenerative fashion remains out of reach.

The Hidden Impact of Garment Components

When we think of sustainable clothing, we often focus on the fabric—but true sustainability goes deeper. Every detail in a garment—from zippers and buttons to thread, elastics, and labels—plays a crucial role in its overall environmental footprint.

and heavy-metal dyes.

Though small, these components are far from insignificant. In fact, non-textile elements can account for a notable share of a garment’s total impact, especially when made from synthetic or composite materials that are difficult to recycle or biodegrade. These parts often become the barriers that prevent otherwise eco-friendly garments from entering a circular system [12,13].

Research shows that when brands prioritize natural or recyclable materials in every element, the result is a piece that’s not only lower impact to produce, but also easier to repair, compost, or recover at end-of-life [13]. For a garment to break down harmlessly in nature, every layer—every stitch—must be chosen with that goal in mind.

Benefits of Localized Production

Producing garments within a single country offers far-reaching benefits that extend well beyond reducing carbon emissions [14]. Localized production not only minimizes the environmental impact of long-distance transport, but also strengthens local economies, preserves cultural heritage, and enables closer oversight of labor and quality standards.

When fashion stays rooted in place, it can serve as a vehicle for circular economy models—where materials, skills, and value remain within communities rather than being outsourced and diluted [15]. Moreover, local production helps protect and revive ancestral knowledge, such as traditional textile techniques and dyeing methods that are often lost in mass manufacturing [14,15].

Still, the path is clear: when we produce close to home, we don’t just reduce impact—we restore connection between what we wear, who makes it, and the land it comes from.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Preserving Ancestral Knowledge in Textile Practices

Across the Andean region and beyond, Indigenous and pre-Hispanic cultures hold deep-rooted knowledge in sustainable textile creation. From natural dyeing with plants and minerals, to intricate hand weaving, to the careful cultivation and harvesting of native fibers—these practices have been passed down over generations, shaped by a worldview that sees nature not as a resource, but as kin [9,16].

Far from being relics of the past, these traditions offer viable, ecological solutions for today’s fashion challenges. They reflect a system where environmental health and social well-being are deeply interconnected. Handmade processes, local materials, and seasonal rhythms result in textiles that are low-impact, long-lasting, and culturally significant [16].

By integrating Indigenous knowledge into contemporary fashion, we don’t just reduce environmental harm—we also honor identity, heritage, and resilience. These ancestral methods offer a living blueprint for circular and regenerative design, proving that sustainability is not a new concept, but one that has existed for centuries in communities that live in balance with their ecosystems [9,17].

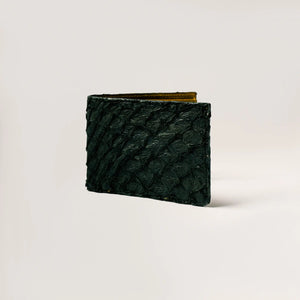

AYA's Commitment to Sustainable Fashion

Each June 5th, the world pauses to reflect on our relationship with the Earth. It’s a reminder that every decision—from what we eat to what we wear—leaves an imprint. But it’s also a celebration: of resilience, of renewal, of the possibility to live and create in harmony with the natural world.

At AYA, this vision isn’t reserved for one day—it guides everything we do. Our approach to fashion is rooted in integrity, reverence, and regeneration. We believe that sustainability must be holistic, touching every part of the process. That’s why we use organic Peruvian Pima cotton with natural and GOTS-certified dyes that protect both ecosystems and people. We guarantee complete traceability by having all our production in Peru, minimizing emissions while uplifting local communities and honor the ancestral knowledge of Andean and Amazonian cultures, weaving heritage into every thread.

This World Environment Day, we reaffirm that commitment by not just creating responsibly, but by sharing knowledge, amplifying tradition, and inviting our community to grow with us—toward a future where fashion truly gives back to the Earth.

How can your fashion choices contribute to a more sustainable and equitable world?

Glossarykeywords

Ancestral Knowledge:

Traditional practices rooted in Indigenous and pre-Hispanic cultures, such as natural dyeing, hand weaving, and fiber cultivation. These methods emphasize harmony with ecosystems and offer sustainable solutions for modern textile challenges

Animal Welfare:

Ethical treatment of animals, guided by principles like the Five Freedoms , ensuring freedom from harm, distress, and exploitation. Critical for ethical wool and fiber production.

Biodiversity:

The variety of life in ecosystems, including plants, insects, and microorganisms. Organic farming enhances biodiversity by avoiding synthetic chemicals and promoting natural habitats.

Biodegradable:

Materials that decompose naturally without harming the environment (e.g., natural dyes, organic cotton). Essential for reducing textile waste.

Carbon Footprint:

Total greenhouse gas emissions produced by a product or process. Fashion’s footprint includes emissions from farming, dyeing, and transportation.

Carbon Sequestration:

Process of capturing CO₂ from the atmosphere. Regenerative farming and organic practices enhance soil’s ability to sequester carbon.

Circular Economy:

System designed to eliminate waste by keeping resources in use (e.g., recycling, repairing). Requires transparency and non-toxic materials.

Conventional Agriculture:

Farming reliant on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and monocultures. Linked to soil degradation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

Certification ensuring textiles meet strict environmental and social criteria, including safe dyeing processes, wastewater treatment, and fair labor practices.

Ecosystem Services:

Benefits provided by healthy ecosystems, such as soil fertility, water purification, and climate regulation. Organic farming enhances these services.

Fast Fashion:

High-speed, low-cost production model driving overconsumption and waste. Criticized for environmental harm and unethical labor practices.

Organic Agriculture:

Farming without synthetic chemicals, emphasizing soil health, crop rotation, and biodiversity. Reduces pesticide use by 97% and nitrate leaching by 50%.

Organic Cotton:

Cotton grown without synthetic pesticides/fertilizers. Uses 91% less water and produces 46% less CO₂ than conventional cotton.

Regenerative Practices:

Farming methods (e.g., rotational grazing, cover cropping) that restore soil health, sequester carbon, and enhance biodiversity.

Supply Chain Transparency:

Disclosure of production processes, from raw materials to finished goods. 54% of consumers link transparency to sustainability.

Traceability:

Tracking a product’s lifecycle to ensure ethical/environmental accountability. Enables verification of organic claims and labor practices.

Xenoestrogens:

Synthetic compounds that imitate estrogen in the body, disrupting natural hormonal balance. Found in many EDCs used in clothing production.

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Authors & Researchers

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

References:

[1] Soil Association. Organic cotton [Internet]. Bristol: Soil Association; c2025 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.soilassociation.org/take-action/organic-living/fashion-textiles/organic-cotton/

[2] Reganold J, Wachter J. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants. 2016;2:15221. doi:10.1038/nplants.2015.221.

[3] Alavanja MCR. Introduction: Pesticides use and exposure, extensive worldwide. Rev Environ Health. 2009;24(4):303–10. doi:10.1515/REVEH.2009.24.4.303.

[4] Maeder P, Fliessbach A, Dubois D, Gunst L, Fried P, Niggli U. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science. 2002 May 31;296(5573):1694–7. doi:10.1126/science.1071148.

[5] Kant R. Textile dyeing industry an environmental hazard. Nat Sci. 2012;4:22–6. doi:10.4236/ns.2012.41004.

[6] Ardila-Leal LD, Poutou-Piñales RA, Pedroza-Rodríguez AM, Quevedo-Hidalgo BE. A brief history of colour, the environmental impact of synthetic dyes and removal by using laccases. Molecules. 2021 Jun 22;26(13):3813. doi:10.3390/molecules26133813. PMID:34206669; PMCID:PMC8270347.

[7] Bechtold, T., & Mussak, R. (2009). Handbook of Natural Colorants. Wiley.

[8] Global Standard GmbH. The Standard [Internet]. Berlin: Global Standard GmbH; c2025 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://global-standard.org/the-standard

[9] Salfino CS. Why leaving a trace is important in fashion. The Robin Report [Internet]. 2024 Sep 24 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://therobinreport.com/why-leaving-a-trace-is-important-in-fashion/

[10] Turker D, Altuntas C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur Manag J. 2014 Oct;32(5):837–49. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2014.02.001.

[11] Niinimäki K, editor. Sustainable fashion in a circular economy. Espoo: Aalto ARTS Books; 2018. Available from: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-0090-9

[12] Fuente: Fletcher, K., & Tham, M. (2019). Fashion and Sustainability: Design for Change. Laurence King Publishing.

[13] Williams GJL, Heidrich O, Sallis PJ. A case study of the open-loop recycling of mixed plastic waste for use in a sports-field drainage system. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2011 Jan;55(2):118–28. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.08.002.

[14] Contreras-Masse R, Ochoa A, Hernandez-Baez I, Ronquillo C, Garcia H, Torres-Escobar R. The sustainable fashion revolution considering circular economy and targeting Generation Z by reusing garments with Acrylan and Terlenka. Int J Combin Optim Probl Inform. 2024;15(2):72–84. doi:10.61467/2007.1558.2024.v15i2.472.

[15] Reyna J. Alpaca breeding in Peru and perspectives for the future. Alpacas Australia. 2005.

[16] Colloredo-Mansfeld R. Consuming: Andean televisions. J Mater Cult. 2003 Sep;8(3):273–84. doi:10.1177/13591835030083003.

[17] Volckhausen T. Indigenous-made film explores traditional textile making in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Mongabay [Internet]. 2019 Feb 28 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/02/indigenous-made-film-traditional-textile-production-in-ecuadorian-amazon/

Glossarykeywords

Ancestral Knowledge:

Traditional practices rooted in Indigenous and pre-Hispanic cultures, such as natural dyeing, hand weaving, and fiber cultivation. These methods emphasize harmony with ecosystems and offer sustainable solutions for modern textile challenges

Animal Welfare:

Ethical treatment of animals, guided by principles like the Five Freedoms , ensuring freedom from harm, distress, and exploitation. Critical for ethical wool and fiber production.

Biodiversity:

The variety of life in ecosystems, including plants, insects, and microorganisms. Organic farming enhances biodiversity by avoiding synthetic chemicals and promoting natural habitats.

Biodegradable:

Materials that decompose naturally without harming the environment (e.g., natural dyes, organic cotton). Essential for reducing textile waste.

Carbon Footprint:

Total greenhouse gas emissions produced by a product or process. Fashion’s footprint includes emissions from farming, dyeing, and transportation.

Carbon Sequestration:

Process of capturing CO₂ from the atmosphere. Regenerative farming and organic practices enhance soil’s ability to sequester carbon.

Circular Economy:

System designed to eliminate waste by keeping resources in use (e.g., recycling, repairing). Requires transparency and non-toxic materials.

Conventional Agriculture:

Farming reliant on synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and monocultures. Linked to soil degradation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

Certification ensuring textiles meet strict environmental and social criteria, including safe dyeing processes, wastewater treatment, and fair labor practices.

Ecosystem Services:

Benefits provided by healthy ecosystems, such as soil fertility, water purification, and climate regulation. Organic farming enhances these services.

Fast Fashion:

High-speed, low-cost production model driving overconsumption and waste. Criticized for environmental harm and unethical labor practices.

Organic Agriculture:

Farming without synthetic chemicals, emphasizing soil health, crop rotation, and biodiversity. Reduces pesticide use by 97% and nitrate leaching by 50%.

Organic Cotton:

Cotton grown without synthetic pesticides/fertilizers. Uses 91% less water and produces 46% less CO₂ than conventional cotton.

Regenerative Practices:

Farming methods (e.g., rotational grazing, cover cropping) that restore soil health, sequester carbon, and enhance biodiversity.

Supply Chain Transparency:

Disclosure of production processes, from raw materials to finished goods. 54% of consumers link transparency to sustainability.

Traceability:

Tracking a product’s lifecycle to ensure ethical/environmental accountability. Enables verification of organic claims and labor practices.

Xenoestrogens:

Synthetic compounds that imitate estrogen in the body, disrupting natural hormonal balance. Found in many EDCs used in clothing production.

Glossarykeywords

Bamboo:

The term "bamboo fabric" generally refers to a variety of textiles made from the bamboo plant. Most bamboo fabric produced worldwide is bamboo viscose, which is economical to produce, although it has environmental drawbacks and poses occupational hazards.

Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs):

They are rod-shaped nanoparticles derived from cellulose. They are biodegradable and renewable materials used in various fields, such as construction, medicine, and crude oil separation.

Circularity in the Textile Value Chain:

It seeks to design durable, recyclable, and long-lasting textiles. The goal is to create a closed-loop system where products are reused and reincorporated into production.

Cotton:

A soft white fibrous substance that surrounds the seeds of a tropical and subtropical plant and is used as textile fiber and thread for sewing.

Fertilizers:

These are nutrient-rich substances used to improve soil characteristics for better crop development. They may contain chemical additives, although there are new developments in the use of organic substances in their production.

Jute:

It is a fiber derived from the jute plant. This plant is composed of long, soft, and lustrous plant fibers that can be spun into thick, strong threads. These fibers are often used to make burlap, a thick, inexpensive material used for bags, sacks, and other industrial purposes. However, jute is a more refined version of burlap, with a softer texture and a more polished appearance.

Hemp:

Industrial hemp is used to make clothing fibers. It is the product of cultivating one of the subspecies of the hemp plant for industrial purposes.

Linen:

It is a plant fiber that comes from the plant of the same name. It is very durable and absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Thanks to these properties, it is comfortable to wear in warm climates and is valued for making clothing.

Organic Cotton:

It is grown with natural seeds, sustainable irrigation methods, and no pesticides or other harmful chemicals are used in its cultivation. As a result, organic cotton is presented as a healthier alternative for the skin.

Pesticides:

It is a substance used to control, eliminate, repel, or prevent pests. Industry uses chemical pesticides for economic reasons.

Subsidy:

It can be defined as any government assistance or incentive, in cash or kind, towards private sectors - producers or consumers - for which the Government does not receive equivalent compensation in return.

The International Day of Zero Waste:

It is celebrated annually on March 30. The day's goal is to promote sustainable consumption and production and raise awareness about zero-waste initiatives.

UNEP:

The United Nations Environment Programme is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental problems within the United Nations system.

Water-Intensive Practices:

These are activities that consume large amounts of water. These practices can have significant environmental impacts, especially in water-scarce regions.

World Water Day:

It is an international celebration of awareness in the care and preservation of water that has been celebrated annually on March 22 since 1993.

Glossarykeywords

Artisan:

A skilled craftsperson who makes products by hand, often using traditional methods passed down through generations.

Dignity:

The state of being worthy of respect. In fashion, it refers to treating workers as valuable human beings, not disposable labor.

Exploitation:

The unfair treatment or use of someone for personal gain, especially by paying them unfairly or subjecting them to unsafe conditions.

Fair trade:

A global movement and certification system that promotes ethical, transparent, and sustainable business practices for producers and workers.

Living wage:

A salary that covers the basic needs of a worker and their family, including housing, food, education, and healthcare.

Overproduction:

The excessive manufacture of goods beyond demand, common in fast fashion, leading to waste and environmental damage.

Transparency:

The practice of openly sharing information about sourcing, production, and labor conditions to allow accountability and informed decisions.

Slow fashion:

A movement that promotes mindful, sustainable, and ethical production and consumption of clothing, focusing on quality over quantity.

Glossarykeywords

Air Dye:

A waterless dyeing technology that uses air to apply color to textiles, eliminating wastewater and reducing chemical use.

Automation in Textile Production:

The use of AI, robotics, and machine learning to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and lower production costs in the fashion industry.

Carbon Emissions:

Greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), released by industrial processes, transportation, and manufacturing, contributing to climate change.

Circular Economy:

A production and consumption model that minimizes waste and maximizes resource efficiency by designing products for durability, reuse, repair, and recycling.

CO₂ Dyeing (DyeCoo):

A sustainable dyeing technology that uses pressurized carbon dioxide instead of water, significantly reducing water waste and pollution.

Ethical Fashion:

Clothing produced in a way that considers the welfare of workers, animals, and the environment, ensuring fair wages and responsible sourcing.

Fast Fashion:

A mass production model that delivers low-cost, trend-based clothing at high speed, often leading to waste, environmental pollution, and unethical labor practices.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

A leading certification for organic textiles that ensures responsible farming practices, sustainable processing, and fair labor conditions.

Greenwashing:

A misleading marketing strategy used by companies to appear more environmentally friendly than they actually are, often exaggerating sustainability claims.

Nanobubble Technology:

A textile treatment method that applies chemicals and dyes using microscopic bubbles, reducing water and chemical usage.

Natural Dyes:

Dyes derived from plants, minerals, or insects that are biodegradable and free from toxic chemicals, unlike synthetic dyes.

Ozone Washing:

A low-impact textile treatment that uses ozone gas instead of chemicals and water to bleach or fade denim, reducing pollution and water consumption.

Proximity Manufacturing:

The practice of producing garments close to consumer markets, reducing transportation-related carbon emissions and promoting local economies.

Recycled Polyester (rPET):

Polyester made from post-consumer plastic waste (e.g., bottles), reducing dependence on virgin petroleum-based fibers.

Slow Fashion:

A movement opposing fast fashion, focusing on sustainable, high-quality, and ethically made clothing that lasts longer.

Sustainable Fashion:

Clothing designed and manufactured with minimal environmental and social impact, using eco-friendly materials and ethical labor practices.

Upcycling:

The creative reuse of materials or textiles to create new products of equal or higher value, reducing waste without breaking down fibers.

Wastewater Recycling:

The treatment and reuse of water in textile production, minimizing freshwater consumption and reducing pollution.

Zero-Waste Design:

A fashion design approach that maximizes fabric efficiency, ensuring that no textile scraps go to waste during the cutting and sewing process.

References:

[1] Soil Association. Organic cotton [Internet]. Bristol: Soil Association; c2025 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.soilassociation.org/take-action/organic-living/fashion-textiles/organic-cotton/

[2] Reganold J, Wachter J. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants. 2016;2:15221. doi:10.1038/nplants.2015.221.

[3] Alavanja MCR. Introduction: Pesticides use and exposure, extensive worldwide. Rev Environ Health. 2009;24(4):303–10. doi:10.1515/REVEH.2009.24.4.303.

[4] Maeder P, Fliessbach A, Dubois D, Gunst L, Fried P, Niggli U. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science. 2002 May 31;296(5573):1694–7. doi:10.1126/science.1071148.

[5] Kant R. Textile dyeing industry an environmental hazard. Nat Sci. 2012;4:22–6. doi:10.4236/ns.2012.41004.

[6] Ardila-Leal LD, Poutou-Piñales RA, Pedroza-Rodríguez AM, Quevedo-Hidalgo BE. A brief history of colour, the environmental impact of synthetic dyes and removal by using laccases. Molecules. 2021 Jun 22;26(13):3813. doi:10.3390/molecules26133813. PMID:34206669; PMCID:PMC8270347.

[7] Bechtold, T., & Mussak, R. (2009). Handbook of Natural Colorants. Wiley.

[8] Global Standard GmbH. The Standard [Internet]. Berlin: Global Standard GmbH; c2025 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://global-standard.org/the-standard

[9] Salfino CS. Why leaving a trace is important in fashion. The Robin Report [Internet]. 2024 Sep 24 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://therobinreport.com/why-leaving-a-trace-is-important-in-fashion/

[10] Turker D, Altuntas C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur Manag J. 2014 Oct;32(5):837–49. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2014.02.001.

[11] Niinimäki K, editor. Sustainable fashion in a circular economy. Espoo: Aalto ARTS Books; 2018. Available from: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-60-0090-9

[12] Fuente: Fletcher, K., & Tham, M. (2019). Fashion and Sustainability: Design for Change. Laurence King Publishing.

[13] Williams GJL, Heidrich O, Sallis PJ. A case study of the open-loop recycling of mixed plastic waste for use in a sports-field drainage system. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2011 Jan;55(2):118–28. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.08.002.

[14] Contreras-Masse R, Ochoa A, Hernandez-Baez I, Ronquillo C, Garcia H, Torres-Escobar R. The sustainable fashion revolution considering circular economy and targeting Generation Z by reusing garments with Acrylan and Terlenka. Int J Combin Optim Probl Inform. 2024;15(2):72–84. doi:10.61467/2007.1558.2024.v15i2.472.

[15] Reyna J. Alpaca breeding in Peru and perspectives for the future. Alpacas Australia. 2005.

[16] Colloredo-Mansfeld R. Consuming: Andean televisions. J Mater Cult. 2003 Sep;8(3):273–84. doi:10.1177/13591835030083003.

[17] Volckhausen T. Indigenous-made film explores traditional textile making in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Mongabay [Internet]. 2019 Feb 28 [cited 2025 Jun 5]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/02/indigenous-made-film-traditional-textile-production-in-ecuadorian-amazon/

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

The Truth About Recycled Polyester in Fashion

Discover the hidden costs of recycled polyester. Learn why rPET isn't as sustainable as it seems and what real circular alternatives look like.

Synthetic Fabrics vs. Organic Cotton: Impact on Skin Health

Discover how polyester and other synthetic fabrics can irritate your skin and why organic cotton, especially Pima cotton, is a healthier and safer choice for sensitive skin.

What Peru Whispers: Organic Pima Cotton Grown with Tradition and Care

In the quiet corners of Peru, organic pima cotton is grown with respect for the land. A luxurious, timeless textile waiting to be discovered.

Why Sustainable Fashion Shouldn’t Be Fast Fashion

Recycled materials and green labels won’t fix fast fashion. Discover why real sustainability means slowing down.