Microplastic Pollution from Washing Machines:

An Overlooked Threat

Picture by Joshua Leeman

AYA | NOVEMBER 19, 2024

READING TIME: 6 minutes

We all know that the fashion industry has its environmental downsides, but did you know that your washing machine is also contributing to pollution? That's right! Your washing machine isn't just cleaning your clothes. Every time we wash synthetic clothes, tiny plastic fibers—called microfibers—break off and enter our water systems, eventually making their way into oceans, rivers, and even our food.

What Are Microfibers?

Microfibers are tiny particles that shed from fabrics, typically less than 5 mm in size. They can be either synthetic (like polyester, nylon, and acrylic) or natural (such as cotton, sheep wool, or alpaca wool). Now you might be wondering: “Why should I care about these microfibers?" Well, unlike natural fibers, synthetic fibers do not break down easily and, because they are so small, they sneak through most water filtration systems [1], from filters inside some washing machines to the most sophisticated water treatment plants. And where do they end up? They end up polluting our rivers, seas and therefore, within marine fauna, harming them, as well as every person who feeds on them.

Shedding Microfibers in Washing Machines

Studies have shown that different fabrics release varying amounts of microfibers when washed. Polyamide (nylon) and acetate fabrics shed more microfibers than polyester, with the number of microfibers increasing with higher washing temperatures [2]. Shockingly, washing one garment could release up to 74,000 microfibers per wash, especially when using high temperatures or detergents.

In another study, researchers conducted washing experiments using both front- and top-load home machines, choosing jackets as test garments due to their wide range of polyester construction styles [3]. The study revealed that top-loading washing machines release seven times more microfibers compared to front-loading machines, with 100,000 synthetic jackets releasing approximately 0.65 to 3.91 kg of synthetic microfibers into wastewater treatment plants each day.

The Role of Wastewater Treatment Plants

You might think that wastewater treatment plants can capture these microfibers before they reach our waterways, but the truth is a bit more complicated. A study in 2016 revealed that while modern treatment plants can remove up to 98.4% of microplastics, significant amounts still escape into the environment [4]. In fact, one treatment plant was found to release 65 million microplastics into rivers every single day.

Percentages of microfibres that are filtered per stage in a water treatment plant. [4]

The fibers that make it through the treatment process are then discharged into rivers, lakes, and oceans. Researchers in 2011 further demonstrated that microfibers from washing machines are a major source of microplastic pollution on shorelines worldwide [5]. The close match between synthetic fibers found in coastal sediments and those in wastewater discharge suggests that washing machine effluent is a key pathway for microplastic pollution reaching global shorelines.

Impact of microplastics: A real risk for the health of the planet and for us

These synthetic fibers have become so widespread that they are now found in some of the most remote parts of the world. Microfibers alone are estimated to account for up to 34.8% of all microplastic pollution in the oceans [6], with studies suggesting that, by 2018, between 7,000 and 35,000 tons of plastic were floating across the open-ocean surface [7]. One of the largest accumulation zones is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP) in the North Pacific Ocean, covering approximately 1.6 million km²—about twice the size of Texas or three times that of France [8,9]—and containing an estimated 2.3 to 12.4 kilotons of plastic [7].

Glossarykeywords

Acetate:

A synthetic fiber made from cellulose, a plant material. Acetate is commonly used in fabrics like silk-like clothing.

Ecosystem:

A community of living things (plants, animals, microorganisms) that interact with each other and their environment.

Effluent:

The treated water that is released from wastewater treatment plants into the environment.

Food Chain:

The process by which organisms are eaten by others, transferring energy and nutrients. For example, fish that eat microplastics may eventually be eaten by humans.

Kiloton:

A unit of weight equal to 1,000 tons (or 1 million kilograms).

Persistent Pollutants:

Substances that remain in the environment for a long time and are difficult to break down.

Wastewater Treatment Plant:

A facility that processes sewage to remove contaminants before releasing the water back into the environment.

Plastic debris concentrations in surface waters across the global ocean. Colored circles indicate average plastic concentrations at 442 sampling sites. Gray areas represent predicted plastic accumulation zones based on a global ocean circulation model: dark gray indicates inner accumulation zones, and white areas show non-accumulation zones. Source: Cózar et al., 2014, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In addition, a 2019 study estimated that approximately 1.4 × 10¹⁷ microfibers are released into the ocean each year from washing synthetic garments [10], which equates to about 17 million microfibers for every person on the planet, based on a global population of around 8 billion.

These tiny fibers are not only persistent pollutants in the water but also pose a risk to marine life. Microplastics have been found embedded in the tissues of various marine organisms, including fish and shellfish [10,11,12], which are later consumed by humans. This contamination of the food chain highlights the broader impact of microfiber pollution on both ecosystem health and human well-being.

What Can We Do?

Reducing microfiber pollution requires both individual action and systemic changes:

- Wash at Lower Temperatures: Studies have shown that washing at lower temperatures can reduce microfiber shedding [2].

- Use Front-Loading Washing Machines: These machines tend to release fewer microfibers than top-loading ones [3].

- Install Washing Machine Filters: Some companies are developing filters that can capture microfibers before they enter the wastewater system. These filters can ideally be taken to specialized recycling or waste management centers to ensure safe disposal, rather than simply ending up in a landfill.

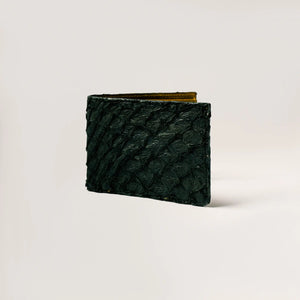

- Choose Natural Fibers: When possible, opt for clothing made from natural fibers like cotton, which releases far fewer microplastics than synthetics.

We can all take steps to minimize this pollution. By choosing better fabrics, washing clothes more carefully, and supporting technological advancements, we can help reduce the impact of this microplastic menace. Read more here.

Glossarykeywords

Acetate:

A synthetic fiber made from cellulose, a plant material. Acetate is commonly used in fabrics like silk-like clothing.

Ecosystem:

A community of living things (plants, animals, microorganisms) that interact with each other and their environment.

Effluent:

The treated water that is released from wastewater treatment plants into the environment.

Food Chain:

The process by which organisms are eaten by others, transferring energy and nutrients. For example, fish that eat microplastics may eventually be eaten by humans.

Kiloton:

A unit of weight equal to 1,000 tons (or 1 million kilograms).

Persistent Pollutants:

Substances that remain in the environment for a long time and are difficult to break down.

Wastewater Treatment Plant:

A facility that processes sewage to remove contaminants before releasing the water back into the environment.

References:

[1] Stuart, B.H. and Ueland, M. (2017). Degradation of Clothing in Depositional Environments. In Taphonomy of Human Remains: Forensic Analysis of the Dead and the Depositional Environment (eds E.M.J. Schotsmans, N. Márquez-Grant and S.L. Forbes). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118953358.ch9

[2] Yang, L., Qiao, F., Lei, K., Li, H., Kang, Y., Cui, S., & An, L. (2019). Microfiber release from different fabrics during washing. Environmental Pollution, 249, 136-143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.011

[3] Hartline, N. L., Bruce, N. J., Karba, S. N., Ruff, E. O., Sonar, S. U., & Holden, P. A. (2016). Microfiber masses recovered from conventional machine washing of new or aged garments. Environmental science & technology, 50(21), 11532-11538. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.6b03045

[4] Murphy, F., Ewins, C., Carbonnier, F., & Quinn, B. (2016). Wastewater treatment works (WwTW) as a source of microplastics in the aquatic environment. Environmental science & technology, 50(11), 5800-5808. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05416

[5] Browne, M. A., Crump, P., Niven, S. J., Teuten, E., Tonkin, A., Galloway, T., & Thompson, R. (2011). Accumulation of microplastic on shorelines woldwide: sources and sinks. Environmental science & technology, 45(21), 9175-9179. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es201811s

[6] Boucher, J. (2017). Primary microplastics in the oceans: a global evaluation of sources. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland (2017), p. 43. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2017.01.en

[7] Cózar, A., Echevarría, F., González-Gordillo, J. I., Irigoien, X., Úbeda, B., Hernández-León, S., Palma, A., Navarro, S., García-de-Lomas, J., Ruiz, A., Fernández-de-Puelles, M., & Duarte, C. M. (2014). Plastic debris in the open ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28), 10239-10244. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.131470511

[8] Lebreton, L., Slat, B., Ferrari, F., Sainte-Rose, B., Aitken, J., Marthouse, R., ... & Reisser, J. (2018). Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Scientific reports, 8(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22939-w

[9] The Ocean Cleanup. The Pacific Garbage Patch. http://surl.li/eavobh

[10] Belzagui, F., Crespi, M., Álvarez, A., Gutiérrez-Bouzán, C., & Vilaseca, M. (2019). Microplastics' emissions: Microfibers’ detachment from textile garments. Environmental Pollution, 248, 1028-1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.02.059

[11] Rochman, C. M., Hoh, E., Kurobe, T., & Teh, S. J. (2013). Ingested plastic transfers hazardous chemicals to fish and induces hepatic stress. Scientific reports, 3(1), 1-7.

[12] Jin, Y., Xia, J., Pan, Z., Yang, J., Wang, W., & Fu, Z. (2018). Polystyrene microplastics induce microbiota dysbiosis and inflammation in the gut of adult zebrafish. Environmental Pollution, 235, 322-329.

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

The Truth About Recycled Polyester in Fashion

Discover the hidden costs of recycled polyester. Learn why rPET isn't as sustainable as it seems and what real circular alternatives look like.

Synthetic Fabrics vs. Organic Cotton: Impact on Skin Health

Discover how polyester and other synthetic fabrics can irritate your skin and why organic cotton, especially Pima cotton, is a healthier and safer choice for sensitive skin.

What Peru Whispers: Organic Pima Cotton Grown with Tradition and Care

In the quiet corners of Peru, organic pima cotton is grown with respect for the land. A luxurious, timeless textile waiting to be discovered.

Why Sustainable Fashion Shouldn’t Be Fast Fashion

Recycled materials and green labels won’t fix fast fashion. Discover why real sustainability means slowing down.