Ecosystems at the Edge:

The Battle for Mangroves and Ponds in a Changing World

.

AYA | APRIL 16, 2025

READING TIME: 6 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz & Lesia Tello

AYA | APRIL 16, 2025

READING TIME: 6 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz & Lesia Tello

On Earth Month, we remember the plight of the most vital yet fragile ecosystems: mangroves and ponds. In this article, we critically examine the innovations and policies emerging to conserve mangroves and ponds, highlighting their invaluable benefits and the urgent need for decisive, globally coordinated action.

The Invaluable Benefits of Mangroves and Ponds

Nature’s Frontline Defenders: Mangroves’s Power

Mangroves are not just trees—they're climate warriors and coastal bodyguards. With their dense, interwoven root systems, they act as natural breakwaters, shielding shorelines from hurricanes, storm surges, and rising sea levels. Their roots trap sediment, slow erosion, and protect infrastructure that artificial barriers often fail to defend [1,2,3,4].

But their power runs deeper. Mangroves are among the planet’s most potent carbon sinks—make up a mere 0.5% of the world’s coastal area, but they store up to ten times more carbon per hectare than terrestrial forests [1,2]. That means every mangrove saved is thousands of tons of carbon locked away from the atmosphere, a powerful blow to climate change. They also play the role of natural water filters. By capturing pollutants, mangroves improve the quality of the water that flows into oceans and aquifers, safeguarding downstream ecosystems like coral reefs [1,2,3].

And when it comes to biodiversity, these coastal forests host everything from crustaceans and mollusks to migratory birds and rare mammals. Their tangle of roots acts as nurseries for countless marine species, many of which are vital for both local consumption and global fish markets. Without mangroves, marine life loses its cradle [1,2,4].

Cultural and economic treasures of mangroves: Protecting Communities with Nature

When we talk about environmental heroes, few ecosystems deserve the title more than mangroves. These tangled coastal forests are more than scenery—they are literal lifelines for millions across the globe [2]. For countless coastal communities, mangroves and adjacent ponds are not a backdrop; they are survival itself.

Fishing, fuelwood collection, small-scale aquaculture, and even community-based tourism—all rely heavily on these ecosystems. Mangroves do not just support livelihoods; they shape cultural identity and determine local economies [5,6]. This is sustainability not as a buzzword, but as a lived, everyday reality.

In regions like the Peruvian Amazon and the Pacific coast, mangroves hold more than ecological value—they are sacred. They preserve the memory of ancestral fishing methods, traditional medicine, and spiritual cosmologies [6]. Destroying these forests is not just an ecological loss; it is an assault on cultural identity and intergenerational knowledge.

Wetlands and ponds surrounding mangroves are repositories of artisanal materials, medicinal plants, and spiritual significance. Their preservation is a matter of climate justice—especially for Indigenous communities who have stewarded them for centuries [1,2,3,5,6].

The financial case for mangrove conservation is clear. Each hectare preserved saves thousands of dollars in storm damage and erosion prevention [8,9]. These ecosystems underpin fisheries that feed millions and sustain ecotourism economies. Ponds contribute to water security and agricultural resilience, reinforcing entire regional economies [7].

To neglect these ecosystems is to invite economic collapse on top of ecological disaster.

Mangroves on the Brink: From Carbon Sink to Dumping Ground

The Dual-Edged Impact of Industrial Practices

Mangroves, the silent warriors of the coastline, are being suffocated—literally. What once stood as vibrant nurseries for marine life and powerful carbon sinks are now cluttered with plastic debris and toxic waste. Plastic pollution wraps around their roots, strangling their ability to filter water, stabilize sediment, and support biodiversity. Worse still, chemicals like heavy metals, herbicides, and petroleum runoff disrupt their delicate balance, reducing growth, reproduction, and species diversity [1,2,10,11].

But it doesn’t stop there. Urban sprawl, dredging, and shrimp farms bulldoze through mangrove belts, leaving behind hypoxic waters and toxic sediments [10]. These pollutants don't just disappear—they accumulate in the soil and wildlife, sabotaging the ecosystem’s ability to store carbon or support life [10,11].

On the other hand, ponds often overlooked in environmental discourse, are no less affected. Used for aquaculture and agriculture, these small yet vital water bodies face a barrage of pollutants—fertilizer runoff, pesticides, and organic waste [101,12,13]. The result? Eutrophication, oxygen depletion, and collapsing aquatic ecosystems. Oil spills and herbicides further toxify these habitats, pushing them to the brink [10,12]. As salinity and sediment contamination rise, the very function of these ponds—to support food security and biodiversity—is threatened.

Fast Fashion’s Filthy Footprint: The Synthetic Thread

Fast fashion isn’t just a trend—it’s a full-blown environmental catastrophe. Polyester alone, made from fossil fuels, not only accelerates climate change but also introduces microplastics into fragile coastal zones, especially near textile hubs. These microscopic invaders clog marine ecosystems, reducing oxygen and killing off biodiversity [1,2,10].

And even when brands shout “eco-collection,” the truth remains: the core production model thrives on speed, excess, and waste. What looks stylish in a store window often begins with environmental devastation in a mangrove swamp or a poisoned pond.

Let’s call it what it is—petroleum is fueling this ecological nightmare. From drilling operations that flatten mangroves to processing plants that leak toxins into water systems, the impact is devastating. Every synthetic fiber starts with crude oil, and that origin story is soaked in deforestation, pollution, and climate disruption [10,13].

The link is clear: the same oil that’s turned into synthetic fabrics poisons the ponds and mangroves meant to protect us from climate extremes. The extraction industry creates a ripple effect that weakens our most effective natural defenses against rising seas and carbon overload.

Policies and Governmental Support for Mangrove and Pond Conservation

Restoration Isn’t Charity—It’s Resistance

In Puerto Níspero, northern Costa Rica, environmental justice is being written by the hands of artisanal fishers. Led by local heroes like Luis Antonio Obando, the community has restored over 140 hectares of mangroves decimated in the '90s by the shrimp industry’s unregulated expansion [14,15]. This is not just recovery—it’s defiance. The largest community-led mangrove revival in Costa Rican history proves that ecological restoration can be grassroots, radical, and deeply local [14,15].

Indonesia: Innovation Rising from the Ruins

Indonesia has lost nearly 40% of its mangroves—victims of aquaculture and unchecked development. Yet it is also a global lab for climate-smart innovation. Marine scientist Sri Rejeki is pioneering “Associate Mangrove Aquaculture” a system that allows for shrimp farming without sacrificing regeneration. Community leaders like Wasito are mobilizing villages to plant, protect, and educate [16].

In Perancak, Indonesia, abandoned shrimp ponds are being brought back to life as mangrove forests. The payoff is massive: over 13 tons of leaf litter and 10 tons of macro-zoobenthos per hectare per year, a sign that the carbon cycle is roaring back. Given that 75% of mangrove carbon is stored in the soil, this isn't just restoration—it’s climate action [16,17]. But every day of delay bleeds carbon into the atmosphere, accelerating the crisis we claim to be solving.

Ecuador’s Experiment in Policy and Power

In the Gulf of Guayaquil, Ecuador is testing a model where politics, science, and local communities collide. The state designates mangroves as Conservation Units—some managed by ministries, others by fishing collectives [2,3,18]. A landmark study by ESPOL University dissected these approaches and found one truth: no conservation strategy works without equity, local ownership, and ecosystem health [18]. The message? Top-down policy without community roots is destined to fail.

Nature-Based Solutions: Beyond the Buzzword

From Latin America to West Africa, mangrove restoration strategies are evolving fast:

- Ecological Mangrove Restoration (EMR): Letting nature lead through tidal restoration, not just replanting [2,19].

- Science + Ancestral Knowledge: Programs like MangRes fuse traditional ecological wisdom with cutting-edge science [20].

- Integrated Restoration Frameworks: Planning, action, and monitoring are now the holy trinity of resilient restoration [21].

- Mangroves as NbS: Now recognized as critical tools for climate resilience, mangroves are entering the global climate finance stage [11,19].

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

The Global Picture: A Patchwork of Progress and Collapse

Here are two completely contrasting examples: On the one hand, in Benin, a hydrological restoration program near Djegbadji boasts an 80% success rate with 50,000 seedlings planted [22,23]. In contrast, in Mexico, policy inconsistency and natural disasters have led to catastrophic mangrove losses—Puerto Marqués has lost 60% of its cover. A clear sign that global efforts are not aligned [24,25].

In the Amazon—Peru and Brazil—, urbanization and pollution strangle some of the world’s most valuable coastal buffers. Brazil’s Amazon Fund channels funds into mangrove protection and sustainable use [26,27]. And Peru’s Government-Indigenous Alliances are creating national protections grounded in traditional stewardship, but driven and monitored by private and external initiatives [28].

But too many nations—like the U.S.—still rely on voluntary standards. In the United States, for instance, the current regulatory framework often relies on voluntary private standards rather than stringent public policies. This has led to a patchwork of protections that vary widely by state and city, weakening the overall impact of conservation efforts [29,30].

Moreover, political shifts, such as those witnessed during the Trump era and through the withdrawal of some countries from international climate agreements, have disrupted global momentum towards sustainable practices. Such policy vacuums and inconsistent enforcement undermine efforts to protect crucial ecosystems, leaving mangroves and ponds vulnerable to exploitation and degradation [31].

Final Reflection: The Urgent Need for Accountability

The fate of our tropical ecosystems hangs in the balance. Mangroves and ponds are not only repositories of incredible biodiversity and cultural heritage; they are vital to the survival of our planet.

At AYA, we recognize that safeguarding our natural world is not just an environmental imperative—it’s a moral duty. The well-being of our planet, and the future of generations to come, depends on our capacity to protect and restore these living legacies.

How long can we ignore the warning signs as our mangroves and coastal ponds vanish beneath the weight of our unbridled consumption?

Glossarykeywords

Aquaculture:

It is the farming of aquatic organisms such as fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants in controlled environments.

Carbon Sequestration:

This is the process of capturing and storing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and is a key process for reducing the amount of CO2 in the air and slowing climate change.

Climate Change:

Refers to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. These shifts can be natural, but since the 1800s, human activities have been the main 1 driver, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels.

Fuelwood Collection:

This is the activity of gathering wood to be used as fuel for cooking and heating.

Indigenous Communities:

They are distinct groups of people with historical continuity to pre-colonial or pre-settler societies, who maintain their unique cultural, social, and often political characteristics and are typically the original inhabitants of a particular territory.

Natural Breakwaters:

They are naturally occurring landforms or features (like reefs, sandbars, or rocky outcrops) that reduce the force of waves before they reach the coastline.

Pond:

It is a small body of still water, usually smaller than a lake. It can be natural or artificially created.

Spiritual Cosmologies:

Refer to belief systems or worldviews that explain the origin, nature, and structure of the universe and humanity's place within it, often involving supernatural beings, forces, or dimensions. They provide a framework for understanding existence, purpose, and the relationship between the physical and spiritual realms.

The Artisanal Textile Industry:

It consists of the production of textiles and clothing by artisans, using traditional techniques and methods, in order to manufacture products that are usually unique and made with high-quality materials.

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Lesia Tello

Biologist and researcher specializing in biochemistry, with a master’s degree in education. Passionate about scientific inquiry, she explores the complexities of life and the processes that sustain it. Her work focuses on the intersection of science, education, and communication, making scientific knowledge accessible and impactful.

Authors & Researchers

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Lesia Tello

Biologist and researcher specializing in biochemistry, with a master’s degree in education. Passionate about scientific inquiry, she explores the complexities of life and the processes that sustain it. Her work focuses on the intersection of science, education, and communication, making scientific knowledge accessible and impactful.

References:

[1] World Wildlife Fund. Mangroves for Community and Climate [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Wildlife Fund; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.worldwildlife.org/initiatives/mangroves-for-community-and-climate

[2] Global Mangrove Alliance. The State of the World’s Mangroves [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.mangrovealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/The-State-of-the-Worlds-Mangroves-2021-FINAL-1.pdf

[3] The Nature Conservancy. Mangroves of the Caribbean: Vital Protectors of Reefs, Seagrass and Coastal Economies [Internet]. Arlington (VA): The Nature Conservancy; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/caribbean/stories-in-caribbean/exploring-caribbean-mangroves/

[4] National Geographic Partners, LLC. Manglares: qué son y por qué conservarlos [Internet]. 2022 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographicla.com/medio-ambiente/2022/07/manglares-que-son-y-por-que-conservarlo

[5] Wood J. 5 reasons to protect mangrove forests for the future. World Economic Forum [Internet]. 2019 Feb 15 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2019/02/5-reasons-to-protect-mangrove-forests-for-the-future/

[6] Fabiano E, Schulz C, Branas ˜ MM. Wetland spirits and indigenous knowledge: Implications for the conservation of wetlands in the Peruvian Amazon. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100107

[7] Wang F, Harindintwali JD, Wei K, Ni J, Zhang L, Gupta P, et al. Climate change: Strategies for mitigation and adaptation. Innovation Geoscience. 2023;1(1):100015. https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2023.100015.

[8] United Nations Environment Programme. An inside look at the beauty and benefits of mangroves [Internet]. 25 Jul 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/inside-look-beauty-and-benefits-mangroves

[9] Brigham Young University. Emergency measures needed to rescue Great Salt Lake from ongoing collapse [Internet]. Provo (UT): Brigham Young University; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://pws.byu.edu/great-salt-lake

[10] Maiti SK, Chowdhury A. Effects of anthropogenic pollution on mangrove biodiversity: A review. J Environ Prot. 2013;4(12):1428–1434. doi:10.4236/jep.2013.412163

[11] United Nations Environment Programme. Coastal crisis: Mangroves at risk [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/coastal-crisis-mangroves-risk

[12] Szafranski GT, Granek EF. Contamination in mangrove ecosystems: A synthesis of literature reviews across multiple contaminant categories. Mar Pollut Bull. 2023 Nov;196:115595. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115595.

[13] Florida Museum. Impacts on Mangroves [Internet]. Gainesville (FL): University of Florida; [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/southflorida/habitats/mangroves/impacts/

[14] Solano DM. Fishing community in Costa Rica restores mangroves as a form of conservation. Mongabay Latam [Internet]. 2022 Jun 9 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://es.mongabay.com/2022/06/comunidad-pesquera-en-costa-rica-restaura-manglares-conservacion/

[15] Obando Campos AA. What happened after the ban on bottom trawling? Transformations in the livelihoods of artisanal and semi-industrial fishers following marine fisheries policies in the Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica [master’s thesis]. Quito (Ecuador): Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO Ecuador; 2021. 133 p. Spanish.

[16] Rahman M. Indonesia's fishers harness protective power of mangrove forests [Internet]. DW. 2022 Jan 19 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/indonesias-fishers-harness-protective-power-of-mangrove-forests/a-60500759

[17] Kusmana C, Kamal M, Putri AI, Gusmara D. Assessment of restored mangrove forests in abandoned aquaculture ponds in Perancak, Indonesia. Global Seafood Alliance Advocate. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/assessment-of-restored-mangrove-forests-in-abandoned-aquaculture-ponds-in-perancak-indonesia/

[18] Herrera P, Calles A, Pozo M, Villa G, Ortega D, Coronel J, Almeida M. Public Policy for Mangrove Conservation and the Well-being of Fishers and Gatherers in the Gulf of Guayaquil. Guayaquil (Ecuador): Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL), Faculty of Life Sciences; Ministry of Environment; Conservation International Ecuador; 2017 Aug.

[19] Lewis RR, Brown B. Ecological Mangrove Rehabilitation: A Field Manual for Practitioners. 1st ed. Copyleft © 2014.

[20] UNESCO. UNESCO-MaNgRes project: Combining scientific expertise, local knowledge and community involvement [Internet]. Paris: UNESCO; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-mangres-project-combining-scientific-expertise-local-knowledge-and-community-involvement

[21] Park K, Lee KS. Development of sustainable integrated design framework for stream restoration. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):674. doi:10.3390/su11030674.

[22] Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Wetlands restoration: unlocking the untapped potential of the Earth’s most valuable ecosystem [Internet]. Gland, Switzerland: Ramsar Convention Secretariat; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/factsheet_wetland_restoration_general_e_0.pdf

[23] Adite A, Imorou‑Toko I, Gbankoto A. Fish Assemblages in the Degraded Mangrove Ecosystems of the Coastal Zone, Benin, West Africa: Implications for Ecosystem Restoration and Resources Conservation. J Environ Prot [Internet]. 2013 Dec;4(12).

[24] Vargas-del-Río D, Brenner L. Mexican communities and public policies in mangroves: between conservation and tourism [Internet]. Estado & comunes : Revista de políticas y problemas públicos. 2024;2(19):77–99.

[25] Ortuño López G. As Acapulco’s mangroves disappear, Mexico takes strides to protect its coastal forests [Internet]. Mongabay; 2025 Apr 8 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/2025/04/as-acapulcos-mangroves-disappear-mexico-takes-strides-to-protect-its-coastal-forests/

[26] Amazon Fund [Internet]. Brasília: Amazon Fund; [date unknown] [cited 2025 Apr 16].

[27]

Mongabay.com. Brazil’s Amazon shipping plan faces criticism for environmental and social impact [Internet]. Mongabay; 2025 Jan 15 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/brazils-amazon-shipping-plan-faces-criticism-for-environmental-and-social-impact/

[28] Badia i Dalmases F. Time is water: a cross‑border indigenous alliance works to save the Amazon [Internet]. Pulitzer Center; 2024 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/time-water-cross-border-indigenous-alliance-works-save-amazon

[29] United States Government Accountability Office. Textile Waste: Federal Entities Should Collaborate on Reduction and Recycling Efforts: Report to Congressional Requesters. Washington (DC): U.S. Government Accountability Office; 2024 Dec. Report No.: GAO‑25‑107165.

[30] DeConcini C, Rennicks J, Hyman G. Trump May Thwart Federal Climate Action, but Opportunities for Progress Remain [Internet]. World Resources Institute; 2024 Nov 13 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.wri.org/insights/trump-climate-action-setbacks-opportunities-us

[31] Larch M, Wanne J. The consequences of non‑participation in the Paris Agreement. Eur Econ Rev. 2024 Apr;163:104699. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2024.104699.

Glossarykeywords

Bamboo:

The term "bamboo fabric" generally refers to a variety of textiles made from the bamboo plant. Most bamboo fabric produced worldwide is bamboo viscose, which is economical to produce, although it has environmental drawbacks and poses occupational hazards.

Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs):

They are rod-shaped nanoparticles derived from cellulose. They are biodegradable and renewable materials used in various fields, such as construction, medicine, and crude oil separation.

Circularity in the Textile Value Chain:

It seeks to design durable, recyclable, and long-lasting textiles. The goal is to create a closed-loop system where products are reused and reincorporated into production.

Cotton:

A soft white fibrous substance that surrounds the seeds of a tropical and subtropical plant and is used as textile fiber and thread for sewing.

Fertilizers:

These are nutrient-rich substances used to improve soil characteristics for better crop development. They may contain chemical additives, although there are new developments in the use of organic substances in their production.

Jute:

It is a fiber derived from the jute plant. This plant is composed of long, soft, and lustrous plant fibers that can be spun into thick, strong threads. These fibers are often used to make burlap, a thick, inexpensive material used for bags, sacks, and other industrial purposes. However, jute is a more refined version of burlap, with a softer texture and a more polished appearance.

Hemp:

Industrial hemp is used to make clothing fibers. It is the product of cultivating one of the subspecies of the hemp plant for industrial purposes.

Linen:

It is a plant fiber that comes from the plant of the same name. It is very durable and absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Thanks to these properties, it is comfortable to wear in warm climates and is valued for making clothing.

Organic Cotton:

It is grown with natural seeds, sustainable irrigation methods, and no pesticides or other harmful chemicals are used in its cultivation. As a result, organic cotton is presented as a healthier alternative for the skin.

Pesticides:

It is a substance used to control, eliminate, repel, or prevent pests. Industry uses chemical pesticides for economic reasons.

Subsidy:

It can be defined as any government assistance or incentive, in cash or kind, towards private sectors - producers or consumers - for which the Government does not receive equivalent compensation in return.

The International Day of Zero Waste:

It is celebrated annually on March 30. The day's goal is to promote sustainable consumption and production and raise awareness about zero-waste initiatives.

UNEP:

The United Nations Environment Programme is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental problems within the United Nations system.

Water-Intensive Practices:

These are activities that consume large amounts of water. These practices can have significant environmental impacts, especially in water-scarce regions.

World Water Day:

It is an international celebration of awareness in the care and preservation of water that has been celebrated annually on March 22 since 1993.

Glossarykeywords

Aquaculture:

It is the farming of aquatic organisms such as fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants in controlled environments.

Carbon Sequestration:

This is the process of capturing and storing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and is a key process for reducing the amount of CO2 in the air and slowing climate change.

Climate Change:

Refers to long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns. These shifts can be natural, but since the 1800s, human activities have been the main 1 driver, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels.

Fuelwood Collection:

This is the activity of gathering wood to be used as fuel for cooking and heating.

Indigenous Communities:

They are distinct groups of people with historical continuity to pre-colonial or pre-settler societies, who maintain their unique cultural, social, and often political characteristics and are typically the original inhabitants of a particular territory.

Natural Breakwaters:

They are naturally occurring landforms or features (like reefs, sandbars, or rocky outcrops) that reduce the force of waves before they reach the coastline.

Pond:

It is a small body of still water, usually smaller than a lake. It can be natural or artificially created.

Spiritual Cosmologies:

Refer to belief systems or worldviews that explain the origin, nature, and structure of the universe and humanity's place within it, often involving supernatural beings, forces, or dimensions. They provide a framework for understanding existence, purpose, and the relationship between the physical and spiritual realms.

The Artisanal Textile Industry:

It consists of the production of textiles and clothing by artisans, using traditional techniques and methods, in order to manufacture products that are usually unique and made with high-quality materials.

Glossarykeywords

Air Dye:

A waterless dyeing technology that uses air to apply color to textiles, eliminating wastewater and reducing chemical use.

Automation in Textile Production:

The use of AI, robotics, and machine learning to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and lower production costs in the fashion industry.

Carbon Emissions:

Greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), released by industrial processes, transportation, and manufacturing, contributing to climate change.

Circular Economy:

A production and consumption model that minimizes waste and maximizes resource efficiency by designing products for durability, reuse, repair, and recycling.

CO₂ Dyeing (DyeCoo):

A sustainable dyeing technology that uses pressurized carbon dioxide instead of water, significantly reducing water waste and pollution.

Ethical Fashion:

Clothing produced in a way that considers the welfare of workers, animals, and the environment, ensuring fair wages and responsible sourcing.

Fast Fashion:

A mass production model that delivers low-cost, trend-based clothing at high speed, often leading to waste, environmental pollution, and unethical labor practices.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

A leading certification for organic textiles that ensures responsible farming practices, sustainable processing, and fair labor conditions.

Greenwashing:

A misleading marketing strategy used by companies to appear more environmentally friendly than they actually are, often exaggerating sustainability claims.

Nanobubble Technology:

A textile treatment method that applies chemicals and dyes using microscopic bubbles, reducing water and chemical usage.

Natural Dyes:

Dyes derived from plants, minerals, or insects that are biodegradable and free from toxic chemicals, unlike synthetic dyes.

Ozone Washing:

A low-impact textile treatment that uses ozone gas instead of chemicals and water to bleach or fade denim, reducing pollution and water consumption.

Proximity Manufacturing:

The practice of producing garments close to consumer markets, reducing transportation-related carbon emissions and promoting local economies.

Recycled Polyester (rPET):

Polyester made from post-consumer plastic waste (e.g., bottles), reducing dependence on virgin petroleum-based fibers.

Slow Fashion:

A movement opposing fast fashion, focusing on sustainable, high-quality, and ethically made clothing that lasts longer.

Sustainable Fashion:

Clothing designed and manufactured with minimal environmental and social impact, using eco-friendly materials and ethical labor practices.

Upcycling:

The creative reuse of materials or textiles to create new products of equal or higher value, reducing waste without breaking down fibers.

Wastewater Recycling:

The treatment and reuse of water in textile production, minimizing freshwater consumption and reducing pollution.

Zero-Waste Design:

A fashion design approach that maximizes fabric efficiency, ensuring that no textile scraps go to waste during the cutting and sewing process.

References:

[1] World Wildlife Fund. Mangroves for Community and Climate [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Wildlife Fund; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.worldwildlife.org/initiatives/mangroves-for-community-and-climate

[2] Global Mangrove Alliance. The State of the World’s Mangroves [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.mangrovealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/The-State-of-the-Worlds-Mangroves-2021-FINAL-1.pdf

[3] The Nature Conservancy. Mangroves of the Caribbean: Vital Protectors of Reefs, Seagrass and Coastal Economies [Internet]. Arlington (VA): The Nature Conservancy; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/caribbean/stories-in-caribbean/exploring-caribbean-mangroves/

[4] National Geographic Partners, LLC. Manglares: qué son y por qué conservarlos [Internet]. 2022 Jul [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographicla.com/medio-ambiente/2022/07/manglares-que-son-y-por-que-conservarlo

[5] Wood J. 5 reasons to protect mangrove forests for the future. World Economic Forum [Internet]. 2019 Feb 15 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2019/02/5-reasons-to-protect-mangrove-forests-for-the-future/

[6] Fabiano E, Schulz C, Branas ˜ MM. Wetland spirits and indigenous knowledge: Implications for the conservation of wetlands in the Peruvian Amazon. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsust.2021.100107

[7] Wang F, Harindintwali JD, Wei K, Ni J, Zhang L, Gupta P, et al. Climate change: Strategies for mitigation and adaptation. Innovation Geoscience. 2023;1(1):100015. https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2023.100015.

[8] United Nations Environment Programme. An inside look at the beauty and benefits of mangroves [Internet]. 25 Jul 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/inside-look-beauty-and-benefits-mangroves

[9] Brigham Young University. Emergency measures needed to rescue Great Salt Lake from ongoing collapse [Internet]. Provo (UT): Brigham Young University; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://pws.byu.edu/great-salt-lake

[10] Maiti SK, Chowdhury A. Effects of anthropogenic pollution on mangrove biodiversity: A review. J Environ Prot. 2013;4(12):1428–1434. doi:10.4236/jep.2013.412163

[11] United Nations Environment Programme. Coastal crisis: Mangroves at risk [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/coastal-crisis-mangroves-risk

[12] Szafranski GT, Granek EF. Contamination in mangrove ecosystems: A synthesis of literature reviews across multiple contaminant categories. Mar Pollut Bull. 2023 Nov;196:115595. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115595.

[13] Florida Museum. Impacts on Mangroves [Internet]. Gainesville (FL): University of Florida; [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/southflorida/habitats/mangroves/impacts/

[14] Solano DM. Fishing community in Costa Rica restores mangroves as a form of conservation. Mongabay Latam [Internet]. 2022 Jun 9 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://es.mongabay.com/2022/06/comunidad-pesquera-en-costa-rica-restaura-manglares-conservacion/

[15] Obando Campos AA. What happened after the ban on bottom trawling? Transformations in the livelihoods of artisanal and semi-industrial fishers following marine fisheries policies in the Gulf of Nicoya, Costa Rica [master’s thesis]. Quito (Ecuador): Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO Ecuador; 2021. 133 p. Spanish.

[16] Rahman M. Indonesia's fishers harness protective power of mangrove forests [Internet]. DW. 2022 Jan 19 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/indonesias-fishers-harness-protective-power-of-mangrove-forests/a-60500759

[17] Kusmana C, Kamal M, Putri AI, Gusmara D. Assessment of restored mangrove forests in abandoned aquaculture ponds in Perancak, Indonesia. Global Seafood Alliance Advocate. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/assessment-of-restored-mangrove-forests-in-abandoned-aquaculture-ponds-in-perancak-indonesia/

[18] Herrera P, Calles A, Pozo M, Villa G, Ortega D, Coronel J, Almeida M. Public Policy for Mangrove Conservation and the Well-being of Fishers and Gatherers in the Gulf of Guayaquil. Guayaquil (Ecuador): Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL), Faculty of Life Sciences; Ministry of Environment; Conservation International Ecuador; 2017 Aug.

[19] Lewis RR, Brown B. Ecological Mangrove Rehabilitation: A Field Manual for Practitioners. 1st ed. Copyleft © 2014.

[20] UNESCO. UNESCO-MaNgRes project: Combining scientific expertise, local knowledge and community involvement [Internet]. Paris: UNESCO; 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-mangres-project-combining-scientific-expertise-local-knowledge-and-community-involvement

[21] Park K, Lee KS. Development of sustainable integrated design framework for stream restoration. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):674. doi:10.3390/su11030674.

[22] Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Wetlands restoration: unlocking the untapped potential of the Earth’s most valuable ecosystem [Internet]. Gland, Switzerland: Ramsar Convention Secretariat; 2021 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.ramsar.org/sites/default/files/documents/library/factsheet_wetland_restoration_general_e_0.pdf

[23] Adite A, Imorou‑Toko I, Gbankoto A. Fish Assemblages in the Degraded Mangrove Ecosystems of the Coastal Zone, Benin, West Africa: Implications for Ecosystem Restoration and Resources Conservation. J Environ Prot [Internet]. 2013 Dec;4(12).

[24] Vargas-del-Río D, Brenner L. Mexican communities and public policies in mangroves: between conservation and tourism [Internet]. Estado & comunes : Revista de políticas y problemas públicos. 2024;2(19):77–99.

[25] Ortuño López G. As Acapulco’s mangroves disappear, Mexico takes strides to protect its coastal forests [Internet]. Mongabay; 2025 Apr 8 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/2025/04/as-acapulcos-mangroves-disappear-mexico-takes-strides-to-protect-its-coastal-forests/

[26] Amazon Fund [Internet]. Brasília: Amazon Fund; [date unknown] [cited 2025 Apr 16].

[27]

Mongabay.com. Brazil’s Amazon shipping plan faces criticism for environmental and social impact [Internet]. Mongabay; 2025 Jan 15 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/short-article/brazils-amazon-shipping-plan-faces-criticism-for-environmental-and-social-impact/

[28] Badia i Dalmases F. Time is water: a cross‑border indigenous alliance works to save the Amazon [Internet]. Pulitzer Center; 2024 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/time-water-cross-border-indigenous-alliance-works-save-amazon

[29] United States Government Accountability Office. Textile Waste: Federal Entities Should Collaborate on Reduction and Recycling Efforts: Report to Congressional Requesters. Washington (DC): U.S. Government Accountability Office; 2024 Dec. Report No.: GAO‑25‑107165.

[30] DeConcini C, Rennicks J, Hyman G. Trump May Thwart Federal Climate Action, but Opportunities for Progress Remain [Internet]. World Resources Institute; 2024 Nov 13 [cited 2025 Apr 16]. Available from: https://www.wri.org/insights/trump-climate-action-setbacks-opportunities-us

[31] Larch M, Wanne J. The consequences of non‑participation in the Paris Agreement. Eur Econ Rev. 2024 Apr;163:104699. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2024.104699.

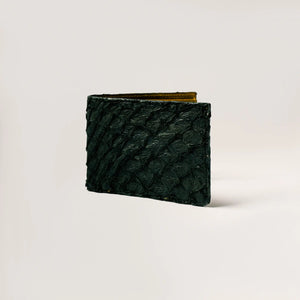

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

EU Green Claims Reversal: What This Means for Greenwashing

The EU's Green Claims Directive is gone. Understand the real impact of greenwashing on your choices and learn how to identify brands that are truly transparent.

France's new law

France has taken a bold step against ultra-fast fashion, targeting brands like Shein with new environmental laws. Discover what this means for sustainability and the future of clothing.

Plastic-Free July: Say No to Single-Use Plastic and Synthetic Clothing

Discover the hidden microplastic footprint of synthetic clothing and fast fashion. Explore the benefits of organic cotton for a truly sustainable wardrobe.

Organic Cotton vs. Conventional Cotton: Environmental, Health & Social Impact

Discover how organic cotton drastically reduces water use, pesticide exposure and environmental harm, while producing longer-lasting, toxin-free garments.