PFAS: The “Forever Chemicals” That Industry

Doesn’t Want You To Know

.

AYA | FEBRUARY 25, 2025

READING TIME: 5 minutes

By Lesia Tello & Jordy Munarriz

AYA | FEBRUARY 25, 2025

READING TIME: 5 minutes

By Lesia Tello & Jordy Munarriz

For decades, corporations have assured us that modern materials—waterproof jackets, grease-resistant food packaging, stain-proof carpets—make life easier. What they don’t tell us? Many of these products come at a hidden cost: the widespread contamination of our environment, our food, and even our bodies by perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “forever chemicals”.

While discussions around PFAS have often focused on drinking water contamination, these chemicals are far more pervasive than most people realize. They’re not just in water; they’re in the food we eat, the air we breathe, the clothes we wear, and the soil that grows our crops [1,2,3,4]. The question is no longer whether we are exposed, but how much, and at what cost?

What Are PFAS?

PFAS are a group of over 4,500 synthetic chemicals used since the 1950s to make products resistant to water, stains, heat, and grease [1,2]. They are commonly found in:

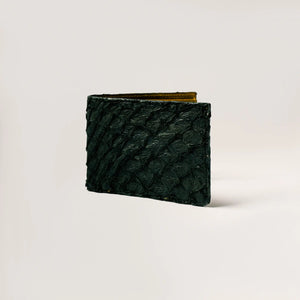

- Textiles: Outdoor gear, rain jackets, uniforms, and stain-resistant fabrics.

- Food Packaging: Fast-food wrappers, pizza boxes, microwave popcorn bags.

- Household Products: Carpets, nonstick cookware, furniture coatings.

- Personal Care Items: Waterproof cosmetics, dental floss.

- Agricultural Contamination: Fertilizers, soil amendments, irrigation water.

PFAS are present in more industries than many people realize. See the table below for a detailed overview of where PFAS are found and their function across industries.

These chemicals are persistent—they don’t break down easily in nature or in our bodies. Once they enter the environment, they stay there for centuries, accumulating in ecosystems and human tissues [1,5,6].

Table: Industrial and Consumer Applications of PFAS

This table presents key industries where PFAS are employed, along with examples of their applications. It is adapted from Glüge et al. (2020). For a complete list and further details, please refer to the original publication.

| Industry Branch | Category and Examples | Function of PFAS |

|---|---|---|

| Textile Production | Dyeing & bleaching of textiles, fiber finishes, waterproof treatments | Anti-foaming, wetting, emulsifying, stain resistance |

| Food Production | Wineries and dairies, irrigation water contamination | Final filtration before bottling, contamination resistance |

| Packaging & Cookware | Nonstick cookware, food packaging, grease-resistant wrappers | Non-stick coating, grease & water repellency |

| Personal Care | Dental floss, toothpaste, cosmetics, waterproof personal care items | Prevents microbial growth, enhances material durability |

| Medical Devices | Catheters, stents, artificial heart pumps, dialysis membranes | Provides flexibility, durability, and low surface tension |

| Automotive Industry | Lubricants, gaskets, air conditioning fluids | Lubrication, heat resistance, improved stability |

| Electronic Industry | Printed circuit boards, capacitors, heat transfer fluids | Cooling of components, solvent deposition, non-reactive coatings |

| Energy Sector | Lithium batteries, solar panels, wind turbine coatings | Prevents thermal runaway, improves energy efficiency |

PFAS in Our Food: The Contamination No One Talks About

Much of the concern around PFAS has been tied to contaminated drinking water, but a major exposure route is through food.

Studies show that PFAS leach into food from packaging, cookware, and even the soil used for farming.

Food Packaging & Takeout Containers

A 2017 study found that nearly 50% of fast-food packaging contains PFAS, particularly items like burger wrappers, fry containers, and microwave popcorn bags [5]. The problem? PFAS migrate into food, especially when exposed to heat and oil, increasing human exposure levels.

Agriculture & Contaminated Crops

PFAS don’t just stay in packaging—they end up in our soil. Industrial pollution, contaminated irrigation water, and the use of sewage sludge as fertilizer have introduced PFAS into farmlands worldwide [2]. Some crops, like lettuce and potatoes, absorb these chemicals more readily than others, making them unexpected sources of PFAS exposure [3].

Teflon & Nonstick Cookware

The convenience of nonstick pans comes at a toxic cost. PFAS-based coatings can degrade under high heat, releasing harmful fumes into food and air [5].

The Health Crisis: What PFAS Do to Our Bodies

Once PFAS enter the body—through food, water, air, or skin contact—they can remain in our system for years. Studies have linked even low levels of exposure to:

- Hormonal Disruptions: Interfering with thyroid function and reproductive health [6,7].

- Immune System Suppression: Lower vaccine effectiveness and increased susceptibility to infections [8].

- Cancer Risk: Possible links to kidney, testicular, and liver cancers [9,10].

- Metabolic Disorders: Increased risk of obesity, high cholesterol, and hypertension [11,12,13].

- Developmental Issues: Affecting fetal growth and increasing the risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women [14,15,16].

The alarming reality? PFAS are now detected in nearly everyone. Studies have found these chemicals in the blood of people across the globe, with up to 99% of analyzed human samples showing measurable levels of PFAS [17,18].

Contamination hotspots often include communities near industrial zones, military bases, and wastewater treatment plants, where PFAS have been released from manufacturing sites, firefighting foam, and landfill leachates [1]. These areas experience particularly high exposure, leading to bioaccumulation in local populations.

Regulations Are Falling Short—And Corporations Know It

The European Union has taken the most aggressive stances against PFAS pollution, proposing a comprehensive ban on approximately 10,000 PFAS chemicals in 2023 under the REACH regulation, which could take effect as early as 2026 [19]. However, the European Commission is considering exemptions for key industries where no viable alternatives exist and a full ban would have disproportionate socio-economic costs, allowing limited PFAS use in sectors like semiconductors, batteries, and renewable energy while aiming to minimize emissions [20].

In contrast, the United States has been slower to act. While the Biden Administration restricted federal procurement of PFAS-containing products in 2021, large-scale manufacturing remains unregulated. The EPA has only set drinking water limits for a handful of PFAS compounds, failing to impose broader restrictions on their use in textiles and other consumer goods [1]. Even more concerning is that many regulations only target specific PFAS chemicals—such as PFOA and PFOS—while leaving thousands of other variants unregulated and widely used. Instead of eliminating PFAS, companies simply replace phased-out compounds with newer, understudied alternatives, whose risks remain unknown [21].

In contrast, the United States has been slower to act. While the Biden Administration restricted federal procurement of PFAS-containing products in 2021, large-scale manufacturing remains unregulated. The EPA has only set drinking water limits for a handful of PFAS compounds, failing to impose broader restrictions on their use in textiles and other consumer goods [1]. Even more concerning is that many regulations only target specific PFAS chemicals—such as PFOA and PFOS—while leaving thousands of other variants unregulated and widely used. Instead of eliminating PFAS, companies simply replace phased-out compounds with newer, understudied alternatives, whose risks remain unknown [21].

Meanwhile, in developing countries—where much of the world’s clothing is produced—weak enforcement of chemical regulations allows PFAS pollution to go unchecked. Nations like Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Vietnam still permit widespread use of PFAS in manufacturing, often supplying textiles to Western brands that claim sustainability while outsourcing production to regions with lax regulations [1].

Ultimately, this outsourcing of environmental harm reflects a system that prioritizes profit over human health and ecological responsibility.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

What Can We Do?

The responsibility of eliminating PFAS should not fall solely on consumers. However, industry accountability remains weak, and governments are slow to act. Here’s what we can do:

- Demand transparency: Hold brands accountable by asking for full disclosure of chemical treatments used in their products.

- Advocate for stronger regulations: Support policies that push for PFAS bans and greater oversight of textile manufacturing.

- Choose natural, untreated fabrics: While no clothing is completely risk-free, natural fibers like organic cotton, hemp, and untreated alpaca wool offer safer alternatives.

- Support ethical brands: Invest in companies actively working to eliminate PFAS from their supply chains.

The fashion industry has long hidden behind greenwashing tactics, using terms like "sustainable" and "eco-friendly" without true accountability. But as PFAS contamination continues to harm people and ecosystems, we must ask ourselves:

Glossarykeywords

Bioaccumulation:

The process by which toxic substances, such as PFAS, build up in the tissues of living organisms over time.

Emissions:

The release of pollutants, including PFAS, into the air, water, or soil, often from industrial activities.

Exposure:

The act of coming into contact with PFAS through food, water, air, or consumer products.

Greenwashing:

A deceptive marketing practice where brands falsely claim to be environmentally friendly while still engaging in harmful practices.

Manufacturing:

The industrial process of producing goods, including textiles and packaging, where PFAS are commonly used.

Nonstick:

A coating applied to cookware and packaging to prevent sticking, often achieved using PFAS-based chemicals.

Persistent:

A characteristic meaning that it does not break down easily and remain in the environment and human body for long periods.

Regulations:

Laws and policies set by governments to control or limit the use of harmful substances like PFAS.

Repellency:

The ability of a surface, such as textiles or packaging, to resist water, stains, or grease, often due to PFAS treatments.

Substitution:

The process of replacing harmful PFAS chemicals with safer alternatives in manufacturing and consumer products.

Textiles:

Fabrics and materials used in clothing and household products, which are often treated with PFAS for water and stain resistance.

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Lesia Tello

Biologist and researcher specializing in biochemistry, with a master’s degree in education. Passionate about scientific inquiry, she explores the complexities of life and the processes that sustain it. Her work focuses on the intersection of science, education, and communication, making scientific knowledge accessible and impactful.

Authors & Researchers

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Lesia Tello

Biologist and researcher specializing in biochemistry, with a master’s degree in education. Passionate about scientific inquiry, she explores the complexities of life and the processes that sustain it. Her work focuses on the intersection of science, education, and communication, making scientific knowledge accessible and impactful.

References:

[1] Newland, A., Khyum, M. M., Halamek, J., & Ramkumar, S. (2023). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—Fibrous substrates. TAPPI J, 22(9), 559-572. https://doi.org/10.32964/tj22.9.559

[2] Glüge, J., Scheringer, M., Cousins, I. T., DeWitt, J. C., Goldenman, G., Herzke, D., ... & Wang, Z. (2020). An overview of the uses of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 22(12), 2345-2373. DOI: 10.1039/D0EM00291G

[3] Ghisi, R., Vamerali, T., & Manzetti, S. (2019). Accumulation of perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) in agricultural plants: A review. Environmental research, 169, 326-341.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.023

[4] Brusseau, M. L., Anderson, R. H., & Guo, B. (2020). PFAS concentrations in soils: Background levels versus contaminated sites. Science of the Total environment, 740, 140017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140017

[5] Seltenrich, N. (2020). PFAS in food packaging: a hot, greasy exposure. Environmental health perspectives, 128(5), 054002. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP6335

[6] Coperchini, F., Croce, L., Ricci, G., Magri, F., Rotondi, M., Imbriani, M., & Chiovato, L. (2021). Thyroid disrupting effects of old and new generation PFAS. Frontiers in endocrinology, 11, 612320. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.612320

[7] Rickard, B. P., Rizvi, I., & Fenton, S. E. (2022). Per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and female reproductive outcomes: PFAS elimination, endocrine-mediated effects, and disease. Toxicology, 465, 153031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2021.153031

[8] Grandjean, P., & Budtz-Jørgensen, E. (2013). Immunotoxicity of perfluorinated alkylates: calculation of benchmark doses based on serum concentrations in children. Environmental Health, 12, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-12-35

[9] Steenland, K., & Winquist, A. (2021). PFAS and cancer, a scoping review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environmental research, 194, 110690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110690

[10] Winquist, A., Hodge, J. M., Diver, W. R., Rodriguez, J. L., Troeschel, A. N., Daniel, J., & Teras, L. R. (2023). Case–Cohort Study of the Association between PFAS and Selected Cancers among Participants in the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II LifeLink

[11] Averina, M., Brox, J., Huber, S., & Furberg, A. S. (2021). Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and dyslipidemia, hypertension and obesity in adolescents. The Fit Futures study. Environmental research, 195, 110740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.110740

[12] Liu, H., Hu, W., Li, X., Hu, F., Xi, Y., Su, Z., ... & Zhang, C. (2021). Do perfluoroalkyl substances aggravate the occurrence of obesity-associated glucolipid metabolic disease?. Environmental Research, 202, 111724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111724

[13] Canova, C., Di Nisio, A., Barbieri, G., Russo, F., Fletcher, T., Batzella, E., ... & Pitter, G. (2021). PFAS concentrations and cardiometabolic traits in highly exposed children and adolescents. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(24), 12881. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412881

[14] Stein, C. R., Savitz, D. A., Elston, B., Thorpe, P. G., & Gilboa, S. M. (2014). Perfluorooctanoate exposure and major birth defects. Reproductive Toxicology, 47, 15-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.04.006

[15] Zhou, Y. T., Li, R., Li, S. H., Ma, X., Liu, L., Niu, D., & Duan, X. (2022). Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposure affects early embryonic development and offspring oocyte quality via inducing mitochondrial dysfunction. Environment International, 167, 107413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107413

[16] Wang, Y., Jiang, S., Wang, B., Chen, X., & Lu, G. (2023). Comparison of developmental toxicity induced by PFOA, HFPO-DA, and HFPO-TA in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere, 311, 136999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.202.136999

[17] Hansen, K. J., Clemen, L. A., Ellefson, M. E., & Johnson, H. O. (2001). Compound-specific, quantitative characterization of organic fluorochemicals in biological matrices. Environmental science & technology, 35(4), 766-770. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es001489z

[18] Kannan, K., Corsolini, S., Falandysz, J., Fillmann, G., Kumar, K. S., Loganathan, B. G., ... & Aldous, K. M. (2004). Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorochemicals in human blood from several countries. Environmental science & technology, 38(17), 4489-4495. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es0493446

[19] Ruttloff, M., & Burchert, T. (2023). PFAS restriction proposal at EU level. Gleiss Lutz. Retrieved from https://www.gleisslutz.com/en/news-events/know-how/pfas-restriction-proposal-eu-level

[20] Abnett, K., & Burger, L. (2024, May 8). EU Commission eyeing exemptions from "forever chemicals" ban – Welt reports. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-commission-eyeing-exemptions-forever-chemicals-ban-welt-reports-2024-05-08/

[21] Scheringer, M., Trier, X., Cousins, I. T., de Voogt, P., Fletcher, T., Wang, Z., & Webster, T. F. (2014). Helsingør Statement on poly-and perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs). Chemosphere, 114, 337-339.

Glossarykeywords

Bioaccumulation:

The process by which toxic substances, such as PFAS, build up in the tissues of living organisms over time.

Greenwashing:

A deceptive marketing practice where brands falsely claim to be environmentally friendly while still engaging in harmful practices.

Manufacturing:

The industrial process of producing goods, including textiles and packaging, where PFAS are commonly used.

Nonstick:

A coating applied to cookware and packaging to prevent sticking, often achieved using PFAS-based chemicals.

Persistent:

A characteristic meaning that it does not break down easily and remain in the environment and human body for long periods.

Repellency:

The ability of a surface, such as textiles or packaging, to resist water, stains, or grease, often due to PFAS treatments.

References:

[1] Newland, A., Khyum, M. M., Halamek, J., & Ramkumar, S. (2023). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—Fibrous substrates. TAPPI J, 22(9), 559-572. https://doi.org/10.32964/tj22.9.559

[2] Glüge, J., Scheringer, M., Cousins, I. T., DeWitt, J. C., Goldenman, G., Herzke, D., ... & Wang, Z. (2020). An overview of the uses of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 22(12), 2345-2373. DOI: 10.1039/D0EM00291G

[3] Ghisi, R., Vamerali, T., & Manzetti, S. (2019). Accumulation of perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) in agricultural plants: A review. Environmental research, 169, 326-341.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.10.023

[4] Brusseau, M. L., Anderson, R. H., & Guo, B. (2020). PFAS concentrations in soils: Background levels versus contaminated sites. Science of the Total environment, 740, 140017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140017

[5] Seltenrich, N. (2020). PFAS in food packaging: a hot, greasy exposure. Environmental health perspectives, 128(5), 054002. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP6335

[6] Coperchini, F., Croce, L., Ricci, G., Magri, F., Rotondi, M., Imbriani, M., & Chiovato, L. (2021). Thyroid disrupting effects of old and new generation PFAS. Frontiers in endocrinology, 11, 612320. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.612320

[7] Rickard, B. P., Rizvi, I., & Fenton, S. E. (2022). Per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and female reproductive outcomes: PFAS elimination, endocrine-mediated effects, and disease. Toxicology, 465, 153031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2021.153031

[8] Grandjean, P., & Budtz-Jørgensen, E. (2013). Immunotoxicity of perfluorinated alkylates: calculation of benchmark doses based on serum concentrations in children. Environmental Health, 12, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-12-35

[9] Steenland, K., & Winquist, A. (2021). PFAS and cancer, a scoping review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environmental research, 194, 110690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110690

[10] Winquist, A., Hodge, J. M., Diver, W. R., Rodriguez, J. L., Troeschel, A. N., Daniel, J., & Teras, L. R. (2023). Case–Cohort Study of the Association between PFAS and Selected Cancers among Participants in the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II LifeLink

[11] Averina, M., Brox, J., Huber, S., & Furberg, A. S. (2021). Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and dyslipidemia, hypertension and obesity in adolescents. The Fit Futures study. Environmental research, 195, 110740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.110740

[12] Liu, H., Hu, W., Li, X., Hu, F., Xi, Y., Su, Z., ... & Zhang, C. (2021). Do perfluoroalkyl substances aggravate the occurrence of obesity-associated glucolipid metabolic disease?. Environmental Research, 202, 111724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111724

[13] Canova, C., Di Nisio, A., Barbieri, G., Russo, F., Fletcher, T., Batzella, E., ... & Pitter, G. (2021). PFAS concentrations and cardiometabolic traits in highly exposed children and adolescents. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(24), 12881. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412881

[14] Stein, C. R., Savitz, D. A., Elston, B., Thorpe, P. G., & Gilboa, S. M. (2014). Perfluorooctanoate exposure and major birth defects. Reproductive Toxicology, 47, 15-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.04.006

[15] Zhou, Y. T., Li, R., Li, S. H., Ma, X., Liu, L., Niu, D., & Duan, X. (2022). Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposure affects early embryonic development and offspring oocyte quality via inducing mitochondrial dysfunction. Environment International, 167, 107413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2022.107413

[16] Wang, Y., Jiang, S., Wang, B., Chen, X., & Lu, G. (2023). Comparison of developmental toxicity induced by PFOA, HFPO-DA, and HFPO-TA in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere, 311, 136999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.202.136999

[17] Hansen, K. J., Clemen, L. A., Ellefson, M. E., & Johnson, H. O. (2001). Compound-specific, quantitative characterization of organic fluorochemicals in biological matrices. Environmental science & technology, 35(4), 766-770. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es001489z

[18] Kannan, K., Corsolini, S., Falandysz, J., Fillmann, G., Kumar, K. S., Loganathan, B. G., ... & Aldous, K. M. (2004). Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorochemicals in human blood from several countries. Environmental science & technology, 38(17), 4489-4495. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es0493446

[19] Ruttloff, M., & Burchert, T. (2023). PFAS restriction proposal at EU level. Gleiss Lutz. Retrieved from https://www.gleisslutz.com/en/news-events/know-how/pfas-restriction-proposal-eu-level

[20] Abnett, K., & Burger, L. (2024, May 8). EU Commission eyeing exemptions from "forever chemicals" ban – Welt reports. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/eu-commission-eyeing-exemptions-forever-chemicals-ban-welt-reports-2024-05-08/

[21] Scheringer, M., Trier, X., Cousins, I. T., de Voogt, P., Fletcher, T., Wang, Z., & Webster, T. F. (2014). Helsingør Statement on poly-and perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs). Chemosphere, 114, 337-339.

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

Plant-Based Power in Sustainable Fashion

An analysis of why cotton remains so popular and how improved water management practices can mitigate the environmental footprint of textile agriculture.

Innovations in Sustainable Fashion: How Technology Is Reshaping Clothing Manufacturing

Discover cutting-edge innovations in sustainable clothing manufacturing, from enzyme-based textile treatments to 3D knitting and digital printing.

Fashion’s Resources: How Sustainable Are They?

Discover the truth about fashion’s resources. Are organic cotton, alpaca wool, and recycled textiles truly sustainable? Explore key materials and eco-friendly practices.

The Fight for Gender Equality: Why We Commemorate International Women’s Day

Discover the real history behind this International Women’s Day, the ongoing struggles of women worldwide, and why ethical fashion matters in this fight.