How Trump’s Plastic Rollback Threatened

Sustainable Fashion Growth

.

AYA | MAY 15, 2025

READING TIME: 5 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz & Lesia Tello

AYA | MAY 15, 2025

READING TIME: 5 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz & Lesia Tello

Over the past decade, sustainable fashion has shifted from niche to mainstream. Today, 74 % of consumers say environmental concerns influence their purchases, and 79 % want an easy way to spot truly green brands [1]. At the same time, sustainable products now account for 17 % of total retail sales—yet they capture 32 % of the market’s growth—and between 2020 and 2025 they expanded 2.7 times faster than conventional goods [1,2]. This momentum has driven many ethical fashion labels to invest heavily in compostable mailers, recycled fabrics, and full circular‑economy models.

But in June 2018, the Trump administration’s Executive Order 13834, “Efficient Federal Operations”, reversed Obama‑era limits on single‑use plastics in federal agencies, citing cost and “operational efficiency,” and in doing so sent a chilling signal to the broader market: plastic was back in favor [3]. Today, the collision of federal deregulation, state‑level bans, trade‑war tariffs, and surging consumer demand poses both profound challenges and unique opportunities for fashion brands committed to real sustainability.

The Trump Administration’s Plastics Rollback

From its first pages, EO 13834 [3] prioritized waste reduction and cost savings across federal buildings, vehicles, and operations—but without mandating the use of biodegradable alternatives in place of conventional plastic utensils, cups, and packaging. Although the Order applied only to federal operations, its ripples reached every corner of the supply chain. Brands that had allocated extra budget for compostable shipping were suddenly faced with a stark question: why bear that premium when the U.S. government itself was reverting to petroleum‑based plastics?

Consumer Demand vs. Plastic Policy

This rollback clashed with what the data showed consumers wanted. Shorr’s 2025 Sustainable Packaging Consumer Report—based on a survey of 2,016 U.S. adults—found that over half (54 %) had deliberately chosen items with eco‑friendly packaging in the prior six months, and an overwhelming 90 % said they are more likely to buy from a brand if its packaging is green [4].

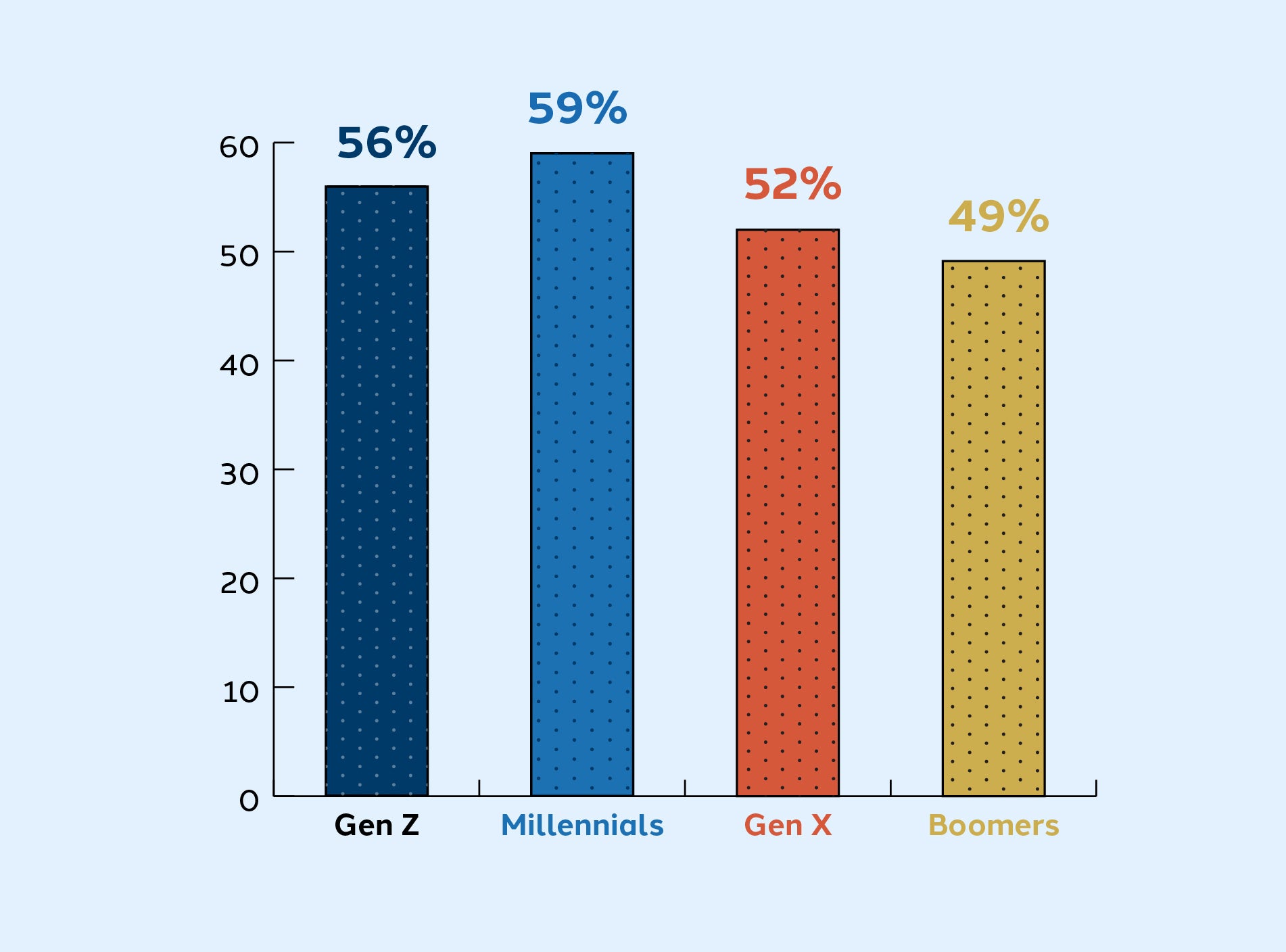

Millennials (59 %) and Gen Z (56 %) drove this trend most strongly, but Gen X (52 %) and even Boomers (49 %) joined the chorus. Meanwhile, 43 % of all consumers are willing to pay a premium for packaging that aligns with their values, and 39 % have switched brands because a competitor offered more sustainable options [5].

The cost pressures did not stop at packaging. Trade‑war tariffs on plant‑based materials further inflated expenses for brands reliant on imported biopolymers and recycled papers. With compostable shipping running up to 20 % more than conventional plastic, many labels faced a brutal calculus: absorb higher costs and cut margins, raise retail prices and risk consumer backlash, or retreat to cheaper plastics to stay competitive [2].

For fast‑moving fashion houses operating on razor‑thin margins, the path of least resistance often seemed to be conventional packaging—even as global competitors in the European Union and China moved aggressively toward plastic bans and taxes.

Percentage of consumers willing to pay a premium for sustainable packaging

Shorr's 2025 Sustainable Packaging Consumer Report: Sustainable Shopping Preference.Source: Shor Hanchett Paper Company.

Global Context: Is the United States Falling Behind?

While the U.S. federal government loosened regulations, dozens of cities and at least seven states—California, New York, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Maryland, and Vermont—enacted their own single‑use plastic restrictions and extended producer responsibility schemes [5,6,7,8]. California’s SB 54, the Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act, signed into law on June 30, 2022, stands out: by 2032 it mandates a 25 % reduction in single‑use plastic packaging, 65 % recycling rates for covered items, and 100 % recyclability or compostability of all primary through tertiary packaging [8,9]. In New York, the statewide ban on plastic bags and foam containers is already yielding results, with plastic bag litter down by over 50 % in some municipalities [8,10].

The regulatory tug‑of‑war is mirrored in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting. Investors poured record capital into sustainable fashion in 2023, with 79 % of institutional investors ranking ESG metrics as a top priority—a figure that has grown steadily since 2020 [11]. Brands touting compostable packaging in their annual sustainability disclosures suddenly found their “green claims” scrutinized against a federal backdrop that still favored plastics. Internationally, these brands are lauded for circular design, yet at home they face accusations of inconsistency. How do you reconcile compliance with California’s SB 54 and Oregons’s bans while also following a federal Order that frames plastics as “operationally efficient”? The result is a complex, costly compliance matrix that can drain resources and distract from genuine innovation.

Despite these headwinds, consumer momentum remains undeniable. By January 2025, sustainable products made up 17 % of the total U.S. retail market—up from 12 % in 2020—and accounted for 32 % of all growth, outpacing conventional items by 2.7 times [2]. The same year, nearly half of American shoppers (49 %) reported buying an eco‑friendly product in the past month, with one‑third (36 %) wanting to buy sustainably but unable to find available options [12,13].

Brands that have survived—and even thrived—through this political seesaw share several traits:

- First, they built deep supply‑chain partnerships to secure reliable sources of plant‑based and recycled inputs, insulating them from tariff shocks [14].

- Second, they embraced transparency, using QR codes and digital passports so consumers can trace packaging back to certified composters or recyclers [15].

- Third, they invested in consumer education, turning packaging into a touchpoint for brand values rather than just a shipping necessity [16,17,18].

- Finally, they lobbied proactively, supporting state‑level EPR legislation that mandates producer responsibility [19]—efforts now paying dividends in the form of level playing fields and shared recycling infrastructures.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Can Sustainable Fashion Thrive in an Era of Plastic Resurgence?

Looking ahead, the industry faces a choice: chase the cheapest plastic each time a federal administration shifts, or commit to a multi‑stakeholder approach that balances cost, compliance, and long‑term brand equity.

At AYA, we fall squarely in the latter camp. We believe true sustainability means using 100 % Pima cotton, sourcing dyes from natural pigments, and shipping in compostable packaging—even if it costs us more in the short term.

The era of excuses is over: we must either commit to genuine sustainability or become just another chapter in the story of fast fashion that forgot its footprint

Glossarykeywords

Biodegradable Materials:

Substances that decompose naturally without harming ecosystems (e.g., plant-based polymers).

Circular Economy:

Model focused on eliminating waste through reuse, recycling, and closed-loop systems.

Consumer Backlash:

Resistance to price hikes for sustainable products, forcing brands to balance ethics and affordability.

Executive Order 13834:

Trump-era policy (2018) reversing Obama’s limits on federal single-use plastics, prioritizing cost over sustainability.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR):

Policies requiring manufacturers to manage recycling or disposal of their products.

Fast Fashion:

Low-cost, rapidly produced clothing with high environmental and social costs.

Greenwashing:

Misleading claims about environmental benefits to appeal to eco-conscious consumers.

QR Codes:

Scannable codes linking to sustainability certifications or supply-chain transparency data.

Single-Use Plastics:

Disposable plastics (e.g., bags, packaging) linked to pollution; targeted by state bans despite federal rollbacks.

Supply-Chain Partnerships:

Collaborations to secure ethical materials and withstand regulatory/tariff disruptions.

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Lesia Tello

Biologist and researcher specializing in biochemistry, with a master’s degree in education. Passionate about scientific inquiry, she explores the complexities of life and the processes that sustain it. Her work focuses on the intersection of science, education, and communication, making scientific knowledge accessible and impactful.

Authors & Researchers

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Lesia Tello

Biologist and researcher specializing in biochemistry, with a master’s degree in education. Passionate about scientific inquiry, she explores the complexities of life and the processes that sustain it. Her work focuses on the intersection of science, education, and communication, making scientific knowledge accessible and impactful.

References:

[1] Engao EL. The consumer-driven demand for sustainability [Internet]. Plastic Bank; 2025 Jan 13 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://plasticbank.com/blog/how-consumer-demand-is-fueling-the-sustainability-shift/

[2] Babar IN. The Great Green Shift: The world moves towards a sustainable future. The Business Standard [Internet]. 2024 Nov 8 [cited 2025 May 15]; Available from: https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/industry/great-green-shift-world-moves-towards-sustainable-future-767670

[3] The White House. The Trump Administration's Environmental Accomplishments [Internet]. Washington (DC): The White House; 2021 Jan [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/210114-Final-Accomplishments-Document.pdf

[4] Shorr Packaging. The 2025 Sustainable Packaging Consumer Report [Internet]. Aurora (IL): Shorr Packaging; 2025 Jan 30 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.shorr.com/resources/blog/sustainable-packaging-consumer-report/

[5] Davenport C, Friedman L. The Trump Administration Is Reversing Nearly 100 Environmental Rules. The New York Times [Internet]. 2020 Jul 15 [cited 2025 May 15]; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/climate/trump-environment-rollbacks-list.html

[6] Oregon Public Broadcasting. California’s plastic bag ban is about to get stricter. Here’s what to know [Internet]. 2024 Sep 26 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.opb.org/article/2024/09/26/california-plastic-bag-ban/

[7] Ocean Protection Council. Plastic Bag Ban Signed [Internet]. Sacramento (CA): California Ocean Protection Council; 2014 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 25].

[8] Bennett P. Plastic bag bans in the US reduced plastic bag use by billions, study finds. World Economic Forum. 2024 Jan 25 [citado 2025 May 15].

[9] CalRecycle. Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act. Packaging EPR Program [Internet]. California: CalRecycle; [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://calrecycle.ca.gov/packaging/packaging-epr/

[10] New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Solid Waste Management Plan: Building the Circular Economy through Sustainable Materials Management. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; 2023 Dec [citado 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://dec.ny.gov/sites/default/files/2023-12/finalsswmp2023.pdf

[11] Segal M. 80% of global investors now have sustainable investment policies in place: Deloitte/Tufts survey. ESG Today. 2024 Apr 2 [cited 2025 May 15]; Available from: https://www.esgtoday.com/80-of-global-investors-now-have-sustainable-investment-policies-in-place-deloitte-tufts-survey/

[12] PricewaterhouseCoopers. Consumers willing to pay 9.7% sustainability premium, even as cost-of-living and inflationary concerns weigh: PwC 2024 Voice of the Consumer Survey. PwC; 2024 May 15 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/news-room/press-releases/2024/pwc-2024-voice-of-consumer-survey.html

[13] GlobeScan. More Americans say they are buying sustainable products in 2025. Insight of the Week. 2025 May 14 [citado 2025 May 15].

[14] Shekarian E, Ijadi B, Zare A, Majava J. Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Industrial Practices. Sustainability. 2022 Jun 28;14(13):7892. doi:10.3390/su14137892.

[15] TraceX Technologies. QR Code Traceability: Building Trust & Transparency. TraceX Technologies. 2024 Sep 25 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://tracextech.com/qr-code-traceability/

[16] Al-Nuaimi SR, Al-Ghamdi SG. Sustainable Consumption and Education for Sustainability in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2022 Jun 14;14(12):7255. doi:10.3390/su14127255.

[17] McKinsey & Company. Consumers care about sustainability — and back it up with their wallets [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/consumers-care-about-sustainability-and-back-it-up-with-their-wallets

[18] Bayazıt A. The role of consumer education in achieving sustainable consumption behavior. J Kirsehir Educ Fac. 2009 Dec 1;10.

[19] Sustainable Packaging Coalition. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Guide. Available from: https://epr.sustainablepackaging.org/

Glossarykeywords

Bamboo:

The term "bamboo fabric" generally refers to a variety of textiles made from the bamboo plant. Most bamboo fabric produced worldwide is bamboo viscose, which is economical to produce, although it has environmental drawbacks and poses occupational hazards.

Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs):

They are rod-shaped nanoparticles derived from cellulose. They are biodegradable and renewable materials used in various fields, such as construction, medicine, and crude oil separation.

Circularity in the Textile Value Chain:

It seeks to design durable, recyclable, and long-lasting textiles. The goal is to create a closed-loop system where products are reused and reincorporated into production.

Cotton:

A soft white fibrous substance that surrounds the seeds of a tropical and subtropical plant and is used as textile fiber and thread for sewing.

Fertilizers:

These are nutrient-rich substances used to improve soil characteristics for better crop development. They may contain chemical additives, although there are new developments in the use of organic substances in their production.

Jute:

It is a fiber derived from the jute plant. This plant is composed of long, soft, and lustrous plant fibers that can be spun into thick, strong threads. These fibers are often used to make burlap, a thick, inexpensive material used for bags, sacks, and other industrial purposes. However, jute is a more refined version of burlap, with a softer texture and a more polished appearance.

Hemp:

Industrial hemp is used to make clothing fibers. It is the product of cultivating one of the subspecies of the hemp plant for industrial purposes.

Linen:

It is a plant fiber that comes from the plant of the same name. It is very durable and absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Thanks to these properties, it is comfortable to wear in warm climates and is valued for making clothing.

Organic Cotton:

It is grown with natural seeds, sustainable irrigation methods, and no pesticides or other harmful chemicals are used in its cultivation. As a result, organic cotton is presented as a healthier alternative for the skin.

Pesticides:

It is a substance used to control, eliminate, repel, or prevent pests. Industry uses chemical pesticides for economic reasons.

Subsidy:

It can be defined as any government assistance or incentive, in cash or kind, towards private sectors - producers or consumers - for which the Government does not receive equivalent compensation in return.

The International Day of Zero Waste:

It is celebrated annually on March 30. The day's goal is to promote sustainable consumption and production and raise awareness about zero-waste initiatives.

UNEP:

The United Nations Environment Programme is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental problems within the United Nations system.

Water-Intensive Practices:

These are activities that consume large amounts of water. These practices can have significant environmental impacts, especially in water-scarce regions.

World Water Day:

It is an international celebration of awareness in the care and preservation of water that has been celebrated annually on March 22 since 1993.

Glossarykeywords

Biodegradable Materials:

Substances that decompose naturally without harming ecosystems (e.g., plant-based polymers).

Consumer Backlash:

Resistance to price hikes for sustainable products, forcing brands to balance ethics and affordability.

Executive Order 13834:

Trump-era policy (2018) reversing Obama’s limits on federal single-use plastics, prioritizing cost over sustainability.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR):

Policies requiring manufacturers to manage recycling or disposal of their products.

QR Codes:

Scannable codes linking to sustainability certifications or supply-chain transparency data.

Single-Use Plastics:

Disposable plastics (e.g., bags, packaging) linked to pollution; targeted by state bans despite federal rollbacks.

Supply-Chain Partnerships:

Collaborations to secure ethical materials and withstand regulatory/tariff disruptions.

Glossarykeywords

Air Dye:

A waterless dyeing technology that uses air to apply color to textiles, eliminating wastewater and reducing chemical use.

Automation in Textile Production:

The use of AI, robotics, and machine learning to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and lower production costs in the fashion industry.

Carbon Emissions:

Greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), released by industrial processes, transportation, and manufacturing, contributing to climate change.

Circular Economy:

A production and consumption model that minimizes waste and maximizes resource efficiency by designing products for durability, reuse, repair, and recycling.

CO₂ Dyeing (DyeCoo):

A sustainable dyeing technology that uses pressurized carbon dioxide instead of water, significantly reducing water waste and pollution.

Ethical Fashion:

Clothing produced in a way that considers the welfare of workers, animals, and the environment, ensuring fair wages and responsible sourcing.

Fast Fashion:

A mass production model that delivers low-cost, trend-based clothing at high speed, often leading to waste, environmental pollution, and unethical labor practices.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

A leading certification for organic textiles that ensures responsible farming practices, sustainable processing, and fair labor conditions.

Greenwashing:

A misleading marketing strategy used by companies to appear more environmentally friendly than they actually are, often exaggerating sustainability claims.

Nanobubble Technology:

A textile treatment method that applies chemicals and dyes using microscopic bubbles, reducing water and chemical usage.

Natural Dyes:

Dyes derived from plants, minerals, or insects that are biodegradable and free from toxic chemicals, unlike synthetic dyes.

Ozone Washing:

A low-impact textile treatment that uses ozone gas instead of chemicals and water to bleach or fade denim, reducing pollution and water consumption.

Proximity Manufacturing:

The practice of producing garments close to consumer markets, reducing transportation-related carbon emissions and promoting local economies.

Recycled Polyester (rPET):

Polyester made from post-consumer plastic waste (e.g., bottles), reducing dependence on virgin petroleum-based fibers.

Slow Fashion:

A movement opposing fast fashion, focusing on sustainable, high-quality, and ethically made clothing that lasts longer.

Sustainable Fashion:

Clothing designed and manufactured with minimal environmental and social impact, using eco-friendly materials and ethical labor practices.

Upcycling:

The creative reuse of materials or textiles to create new products of equal or higher value, reducing waste without breaking down fibers.

Wastewater Recycling:

The treatment and reuse of water in textile production, minimizing freshwater consumption and reducing pollution.

Zero-Waste Design:

A fashion design approach that maximizes fabric efficiency, ensuring that no textile scraps go to waste during the cutting and sewing process.

References:

[1] Engao EL. The consumer-driven demand for sustainability [Internet]. Plastic Bank; 2025 Jan 13 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://plasticbank.com/blog/how-consumer-demand-is-fueling-the-sustainability-shift/

[2] Babar IN. The Great Green Shift: The world moves towards a sustainable future. The Business Standard [Internet]. 2024 Nov 8 [cited 2025 May 15]; Available from: https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/industry/great-green-shift-world-moves-towards-sustainable-future-767670

[3] The White House. The Trump Administration's Environmental Accomplishments [Internet]. Washington (DC): The White House; 2021 Jan [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/210114-Final-Accomplishments-Document.pdf

[4] Shorr Packaging. The 2025 Sustainable Packaging Consumer Report [Internet]. Aurora (IL): Shorr Packaging; 2025 Jan 30 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.shorr.com/resources/blog/sustainable-packaging-consumer-report/

[5] Davenport C, Friedman L. The Trump Administration Is Reversing Nearly 100 Environmental Rules. The New York Times [Internet]. 2020 Jul 15 [cited 2025 May 15]; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/climate/trump-environment-rollbacks-list.html

[6] Oregon Public Broadcasting. California’s plastic bag ban is about to get stricter. Here’s what to know [Internet]. 2024 Sep 26 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.opb.org/article/2024/09/26/california-plastic-bag-ban/

[7] Ocean Protection Council. Plastic Bag Ban Signed [Internet]. Sacramento (CA): California Ocean Protection Council; 2014 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 25].

[8] Bennett P. Plastic bag bans in the US reduced plastic bag use by billions, study finds. World Economic Forum. 2024 Jan 25 [citado 2025 May 15].

[9] CalRecycle. Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act. Packaging EPR Program [Internet]. California: CalRecycle; [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://calrecycle.ca.gov/packaging/packaging-epr/

[10] New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. New York State Solid Waste Management Plan: Building the Circular Economy through Sustainable Materials Management. Albany, NY: New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; 2023 Dec [citado 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://dec.ny.gov/sites/default/files/2023-12/finalsswmp2023.pdf

[11] Segal M. 80% of global investors now have sustainable investment policies in place: Deloitte/Tufts survey. ESG Today. 2024 Apr 2 [cited 2025 May 15]; Available from: https://www.esgtoday.com/80-of-global-investors-now-have-sustainable-investment-policies-in-place-deloitte-tufts-survey/

[12] PricewaterhouseCoopers. Consumers willing to pay 9.7% sustainability premium, even as cost-of-living and inflationary concerns weigh: PwC 2024 Voice of the Consumer Survey. PwC; 2024 May 15 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/news-room/press-releases/2024/pwc-2024-voice-of-consumer-survey.html

[13] GlobeScan. More Americans say they are buying sustainable products in 2025. Insight of the Week. 2025 May 14 [citado 2025 May 15].

[14] Shekarian E, Ijadi B, Zare A, Majava J. Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Industrial Practices. Sustainability. 2022 Jun 28;14(13):7892. doi:10.3390/su14137892.

[15] TraceX Technologies. QR Code Traceability: Building Trust & Transparency. TraceX Technologies. 2024 Sep 25 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://tracextech.com/qr-code-traceability/

[16] Al-Nuaimi SR, Al-Ghamdi SG. Sustainable Consumption and Education for Sustainability in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2022 Jun 14;14(12):7255. doi:10.3390/su14127255.

[17] McKinsey & Company. Consumers care about sustainability — and back it up with their wallets [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/consumers-care-about-sustainability-and-back-it-up-with-their-wallets

[18] Bayazıt A. The role of consumer education in achieving sustainable consumption behavior. J Kirsehir Educ Fac. 2009 Dec 1;10.

[19] Sustainable Packaging Coalition. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Guide. Available from: https://epr.sustainablepackaging.org/

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

The Truth About Recycled Polyester in Fashion

Discover the hidden costs of recycled polyester. Learn why rPET isn't as sustainable as it seems and what real circular alternatives look like.

Synthetic Fabrics vs. Organic Cotton: Impact on Skin Health

Discover how polyester and other synthetic fabrics can irritate your skin and why organic cotton, especially Pima cotton, is a healthier and safer choice for sensitive skin.

What Peru Whispers: Organic Pima Cotton Grown with Tradition and Care

In the quiet corners of Peru, organic pima cotton is grown with respect for the land. A luxurious, timeless textile waiting to be discovered.

Why Sustainable Fashion Shouldn’t Be Fast Fashion

Recycled materials and green labels won’t fix fast fashion. Discover why real sustainability means slowing down.