Why Sustainable Fashion Shouldn’t Be

Fast Fashion

.

AYA | AUGUST 12, 2025

READING TIME: 4 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

AYA | AUGUST 12, 2025

READING TIME: 4 minutes

By Jordy Munarriz

In recent years, the term sustainable fashion has gained visibility. Yet paradoxically, it often appears alongside trends of fast fashion—weekly drops, influencer hauls, and “eco-collections” that still chase quantity over longevity. This dissonance raises an urgent question: can fashion truly be sustainable if it’s still fast?

The short answer: no. And here’s why.

The Environmental Urgency to Slow Down

The fashion industry is one of the most resource-intensive industries globally. Textile production alone is responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions and 20% of wastewater [1,2].

Even so-called sustainable materials are not exempt from scrutiny when used within fast production cycles. Organic cotton, for instance, requires no pesticides and consumes considerably less water than its conventional counterpart [3], but if it’s overproduced, discarded quickly, or blended with synthetics, its benefits are significantly lost and the effort to reduce its impact is sidelined.

The issue is not only what we produce, but how much, how often, and for how long we use it.

Reviews of studies on the actual impacts of reused or recycled textiles emphasize that reducing production and practicing responsible consumption is the most impactful way to lower fashion’s environmental footprint—not just changing the origin of fabrics [4].

Women search for usable clothes amid tons of discarded items in Chile’s Atacama desert. Source: University if Washington.

Why Fast Fashion and Eco Fashion Are Fundamentally Incompatible

Fast fashion isn’t just about speed. It’s a business model designed around volume, immediacy, and disposability. So when large brands launch “green” capsule collections within their usual rapid cycles, the logic remains unsustainable—even if the fabric is recycled or labeled “eco.”

Critics warn of greenwashing when brands promote such lines while maintaining unsustainable core practices. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and France’s DGCCRF have both intensified scrutiny of vague eco-labeling and misleading environmental claims [5,6].

In fact, France recently passed an anti-fast fashion law that fines ultra-fast fashion companies for their social and environmental damage, and bans advertisements that overstate sustainability claims. The aim is clear: slow down the cycle and force brands to be accountable for impact across the supply chain [7].

On the other side of the Atlantic, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission is revising its Green Guides, aiming to tighten regulations on green claims and demand clearer evidence from brands [8].

Fast Fashion's Double Crisis: Waste and Wear

Globally, over 92 million tonnes of textile waste are generated annually [9]. Much of it originates from fast fashion garments discarded after fewer than ten uses. These discarded clothes are rarely recycled. Instead, they end up incinerated, exported to the Global South, or buried in landfills, where they pose long-term environmental and social challenges.

But this crisis isn't just about volume—it's also about quality.

Fast fashion is designed for speed and cost-efficiency, not durability. To maximize profit margins, brands often use low-grade materials and compressed production timelines, resulting in garments that are structurally weak. Even if labeled “organic” or “recycled,” fast-fashion garments that follow the same hyper-consumption model are still problematic. An organic cotton T-shirt that’s worn twice and thrown out is no more sustainable than a conventional one. A dress made from recycled polyester, if poorly constructed and discarded quickly, may still end up leaching microplastics in a landfill for centuries.

In short, the rapid-use, rapid-disposal model of fast fashion undercuts any potential benefit from better materials. It creates a double crisis: a waste problem, due to sheer volume and lack of biodegradability, and a wear problem, where garments are engineered to fail—encouraging the next purchase rather than prolonging the life of what we already have.

The Illusion of Recycled Synthetics

Many brands market recycled polyester as a sustainable breakthrough. However, experts point out that while it may reduce reliance on virgin petroleum, recycled polyester still sheds microplastics—because it will never be biodegradable [11]. So, is extending the life of used polyester in clothing an improvement? Yes. But is it a sustainable one? That’s where the problem lies. If this recycled polyester becomes the raw material for fast fashion garments, its extended life is negligible, and it will ultimately end up in landfills with the same environmental impact as regular polyester clothing. There is no real progress—just a more pleasant narrative with the same ending.

These solutions can delay more tangible changes—such as circular design, repairability, and material transparency—by creating the illusion of progress while sustaining overproduction [12]. Let’s be clear: innovation in repair and recycling should not be dismissed, but it should not be the main banner of fast fashion’s transition toward sustainability.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Garment labels that include recycled polyester.

Toward a Slower, Smarter Wardrobe

Sustainability must be systemic. That means rethinking not just what we wear, but how we value clothing:

- Buy less, choose well. Quality pieces that last for years, not weeks.

- Read the labels. Choose natural, biodegradable materials.

- Question convenience. If something is fast and cheap, someone—or something—paid the price.

- Repair and care. Extend the life of what you already own.

- Support accountability. Favor brands that offer transparency, not tokenism.

Final Reflection: Sustainability is Slow Fashion in Action

Fast fashion and sustainability are incompatible by design. No matter how “green” a collection claims to be, if it's churned out en masse, meant to be replaced in weeks, or hides behind vague claims—it misses the mark.

As consumers, our power lies in resistance. In rejecting disposability. In embracing sustainability.

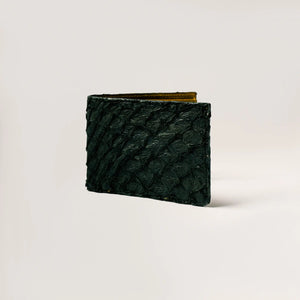

At AYA, we are committed to this path. Our collections are built with Pima organic cotton, grown in the Peruvian valleys, harvested ethically, and designed to last. We don’t chase trends—we build traditions. Because real sustainability isn’t fast. It’s rooted, intentional, and responsible.

Glossarykeywords

Biodegradable:

Able to break down naturally and safely in the environment without leaving harmful residues.

Circular Design:

A design approach focused on creating products that can be reused, repaired, or recycled, minimizing waste and extending lifespan.

Eco-Fashion:

Clothing marketed as environmentally friendly, often using organic or recycled materials—though not always sustainably produced.

Fast Fashion:

A business model based on rapid production, low cost, and high turnover of clothing, often at the expense of quality, labor ethics, and sustainability.

Greenwashing:

A marketing tactic where brands exaggerate or falsely claim environmental benefits to appear more sustainable than they actually are.

Longevity:

The durability and lifespan of a product; in fashion, it refers to how long a garment remains wearable and relevant.

Microplastics:

Tiny plastic particles shed from synthetic materials, including clothing, which pollute water systems and accumulate in ecosystems.

Organic Cotton:

Cotton grown without synthetic pesticides or fertilizers, often using less water than conventional cotton.

Overproduction:

Producing more clothing than is needed or can be sold, leading to excessive waste and environmental strain.

Slow Fashion:

A movement that prioritizes quality, ethical production, and thoughtful consumption over speed and quantity.

Sustainability (in fashion):

The practice of designing, producing, and consuming clothing in ways that minimize environmental and social harm.

Transparency:

A brand's openness about its materials, sourcing, labor practices, and environmental impact.

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

Authors & Researchers

Authors & Researchers

Jordy Munarriz

Environmental Engineer with a master's degree in renewable energy and a specialization in sustainability. Researcher and writer, he combines his technical knowledge with his passion for environmental communication, addressing topics of ecological impact and sustainable solutions in the textile industry and beyond.

References:

[1] European Parliament. The impact of textile production and waste on the environment (infographics) [Internet]. Brussels: European Parliament; 2020 Dec 29 [updated 2024 Mar 21; cited 2025 Aug 12].

[2] Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A new textiles economy: redesigning fashion’s future [Internet]. Cowes (UK): Ellen MacArthur Foundation; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 12].

[3] Textile Exchange. Annual Report 2023 [Internet]. Textile Exchange; 2024 Mar [cited 2025 Aug 12].

[4] Sandin G, Peters GM. Environmental impact of textile reuse and recycling: a review. J Clean Prod. 2018 May 20;184:353–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.266.

[5] Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). Green Claims Code [Internet]. London: CMA UK; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/green-claims-code-making-environmental-claims

[6] DGCCRF France. Surveillance des allégations environnementales [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/dgccrf

[8] BBC News. France votes to ban advertising of fast fashion and fine companies like Shein [Internet]. 2025 Jun 14 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ceq7lqley32o

[9] Federal Trade Commission. Green Guides [Internet]. Washington (DC): FTC [cited 2025 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/truth-advertising/green-guides

[10] Wren B. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain. 2022;4:100032.

[11] Napper IE, Thompson RC. Release of synthetic microplastic fibres from domestic washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2016;112(1-2):39–45.

[12] UNRIC. From petroleum to pollution: the cost of polyester [Internet]. 2024 Dec 17 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://unric.org/en/from-petroleum-to-pollution-the-cost-of-polyester/

[13] Abdelmeguid A, Afy-Shararah M, Salonitis K. Towards circular fashion: management strategies promoting circular behaviour along the value chain. Sustain Prod Consum. 2024 Jul;48:143–56. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2024.05.010.

Glossarykeywords

Biodegradable:

Able to break down naturally and safely in the environment without leaving harmful residues.

Circular Design:

A design approach focused on creating products that can be reused, repaired, or recycled, minimizing waste and extending lifespan.

Eco-Fashion:

Clothing marketed as environmentally friendly, often using organic or recycled materials—though not always sustainably produced.

Fast Fashion:

A business model based on rapid production, low cost, and high turnover of clothing, often at the expense of quality, labor ethics, and sustainability.

Greenwashing:

A marketing tactic where brands exaggerate or falsely claim environmental benefits to appear more sustainable than they actually are.

Longevity:

The durability and lifespan of a product; in fashion, it refers to how long a garment remains wearable and relevant.

Microplastics:

Tiny plastic particles shed from synthetic materials, including clothing, which pollute water systems and accumulate in ecosystems.

Organic Cotton:

Cotton grown without synthetic pesticides or fertilizers, often using less water than conventional cotton.

Overproduction:

Producing more clothing than is needed or can be sold, leading to excessive waste and environmental strain.

Slow Fashion:

A movement that prioritizes quality, ethical production, and thoughtful consumption over speed and quantity.

Sustainability (in fashion):

The practice of designing, producing, and consuming clothing in ways that minimize environmental and social harm.

Transparency:

A brand's openness about its materials, sourcing, labor practices, and environmental impact.

Glossarykeywords

Bamboo:

The term "bamboo fabric" generally refers to a variety of textiles made from the bamboo plant. Most bamboo fabric produced worldwide is bamboo viscose, which is economical to produce, although it has environmental drawbacks and poses occupational hazards.

Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNCs):

They are rod-shaped nanoparticles derived from cellulose. They are biodegradable and renewable materials used in various fields, such as construction, medicine, and crude oil separation.

Circularity in the Textile Value Chain:

It seeks to design durable, recyclable, and long-lasting textiles. The goal is to create a closed-loop system where products are reused and reincorporated into production.

Cotton:

A soft white fibrous substance that surrounds the seeds of a tropical and subtropical plant and is used as textile fiber and thread for sewing.

Fertilizers:

These are nutrient-rich substances used to improve soil characteristics for better crop development. They may contain chemical additives, although there are new developments in the use of organic substances in their production.

Jute:

It is a fiber derived from the jute plant. This plant is composed of long, soft, and lustrous plant fibers that can be spun into thick, strong threads. These fibers are often used to make burlap, a thick, inexpensive material used for bags, sacks, and other industrial purposes. However, jute is a more refined version of burlap, with a softer texture and a more polished appearance.

Hemp:

Industrial hemp is used to make clothing fibers. It is the product of cultivating one of the subspecies of the hemp plant for industrial purposes.

Linen:

It is a plant fiber that comes from the plant of the same name. It is very durable and absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Thanks to these properties, it is comfortable to wear in warm climates and is valued for making clothing.

Organic Cotton:

It is grown with natural seeds, sustainable irrigation methods, and no pesticides or other harmful chemicals are used in its cultivation. As a result, organic cotton is presented as a healthier alternative for the skin.

Pesticides:

It is a substance used to control, eliminate, repel, or prevent pests. Industry uses chemical pesticides for economic reasons.

Subsidy:

It can be defined as any government assistance or incentive, in cash or kind, towards private sectors - producers or consumers - for which the Government does not receive equivalent compensation in return.

The International Day of Zero Waste:

It is celebrated annually on March 30. The day's goal is to promote sustainable consumption and production and raise awareness about zero-waste initiatives.

UNEP:

The United Nations Environment Programme is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental problems within the United Nations system.

Water-Intensive Practices:

These are activities that consume large amounts of water. These practices can have significant environmental impacts, especially in water-scarce regions.

World Water Day:

It is an international celebration of awareness in the care and preservation of water that has been celebrated annually on March 22 since 1993.

Glossarykeywords

Artisan:

A skilled craftsperson who makes products by hand, often using traditional methods passed down through generations.

Dignity:

The state of being worthy of respect. In fashion, it refers to treating workers as valuable human beings, not disposable labor.

Exploitation:

The unfair treatment or use of someone for personal gain, especially by paying them unfairly or subjecting them to unsafe conditions.

Fair trade:

A global movement and certification system that promotes ethical, transparent, and sustainable business practices for producers and workers.

Living wage:

A salary that covers the basic needs of a worker and their family, including housing, food, education, and healthcare.

Overproduction:

The excessive manufacture of goods beyond demand, common in fast fashion, leading to waste and environmental damage.

Transparency:

The practice of openly sharing information about sourcing, production, and labor conditions to allow accountability and informed decisions.

Slow fashion:

A movement that promotes mindful, sustainable, and ethical production and consumption of clothing, focusing on quality over quantity.

Glossarykeywords

Air Dye:

A waterless dyeing technology that uses air to apply color to textiles, eliminating wastewater and reducing chemical use.

Automation in Textile Production:

The use of AI, robotics, and machine learning to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and lower production costs in the fashion industry.

Carbon Emissions:

Greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), released by industrial processes, transportation, and manufacturing, contributing to climate change.

Circular Economy:

A production and consumption model that minimizes waste and maximizes resource efficiency by designing products for durability, reuse, repair, and recycling.

CO₂ Dyeing (DyeCoo):

A sustainable dyeing technology that uses pressurized carbon dioxide instead of water, significantly reducing water waste and pollution.

Ethical Fashion:

Clothing produced in a way that considers the welfare of workers, animals, and the environment, ensuring fair wages and responsible sourcing.

Fast Fashion:

A mass production model that delivers low-cost, trend-based clothing at high speed, often leading to waste, environmental pollution, and unethical labor practices.

GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard):

A leading certification for organic textiles that ensures responsible farming practices, sustainable processing, and fair labor conditions.

Greenwashing:

A misleading marketing strategy used by companies to appear more environmentally friendly than they actually are, often exaggerating sustainability claims.

Nanobubble Technology:

A textile treatment method that applies chemicals and dyes using microscopic bubbles, reducing water and chemical usage.

Natural Dyes:

Dyes derived from plants, minerals, or insects that are biodegradable and free from toxic chemicals, unlike synthetic dyes.

Ozone Washing:

A low-impact textile treatment that uses ozone gas instead of chemicals and water to bleach or fade denim, reducing pollution and water consumption.

Proximity Manufacturing:

The practice of producing garments close to consumer markets, reducing transportation-related carbon emissions and promoting local economies.

Recycled Polyester (rPET):

Polyester made from post-consumer plastic waste (e.g., bottles), reducing dependence on virgin petroleum-based fibers.

Slow Fashion:

A movement opposing fast fashion, focusing on sustainable, high-quality, and ethically made clothing that lasts longer.

Sustainable Fashion:

Clothing designed and manufactured with minimal environmental and social impact, using eco-friendly materials and ethical labor practices.

Upcycling:

The creative reuse of materials or textiles to create new products of equal or higher value, reducing waste without breaking down fibers.

Wastewater Recycling:

The treatment and reuse of water in textile production, minimizing freshwater consumption and reducing pollution.

Zero-Waste Design:

A fashion design approach that maximizes fabric efficiency, ensuring that no textile scraps go to waste during the cutting and sewing process.

References:

[1] European Parliament. The impact of textile production and waste on the environment (infographics) [Internet]. Brussels: European Parliament; 2020 Dec 29 [updated 2024 Mar 21; cited 2025 Aug 12].

[2] Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A new textiles economy: redesigning fashion’s future [Internet]. Cowes (UK): Ellen MacArthur Foundation; 2017 [cited 2025 Aug 12].

[3] Textile Exchange. Annual Report 2023 [Internet]. Textile Exchange; 2024 Mar [cited 2025 Aug 12].

[4] Sandin G, Peters GM. Environmental impact of textile reuse and recycling: a review. J Clean Prod. 2018 May 20;184:353–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.266.

[5] Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). Green Claims Code [Internet]. London: CMA UK; 2023 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/green-claims-code-making-environmental-claims

[6] DGCCRF France. Surveillance des allégations environnementales [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.economie.gouv.fr/dgccrf

[8] BBC News. France votes to ban advertising of fast fashion and fine companies like Shein [Internet]. 2025 Jun 14 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ceq7lqley32o

[9] Federal Trade Commission. Green Guides [Internet]. Washington (DC): FTC [cited 2025 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/topics/truth-advertising/green-guides

[10] Wren B. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain. 2022;4:100032.

[11] Napper IE, Thompson RC. Release of synthetic microplastic fibres from domestic washing machines. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2016;112(1-2):39–45.

[12] UNRIC. From petroleum to pollution: the cost of polyester [Internet]. 2024 Dec 17 [cited 2025 Aug 7]. Available from: https://unric.org/en/from-petroleum-to-pollution-the-cost-of-polyester/

[13] Abdelmeguid A, Afy-Shararah M, Salonitis K. Towards circular fashion: management strategies promoting circular behaviour along the value chain. Sustain Prod Consum. 2024 Jul;48:143–56. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2024.05.010.

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

The Truth About Recycled Polyester in Fashion

Discover the hidden costs of recycled polyester. Learn why rPET isn't as sustainable as it seems and what real circular alternatives look like.

Synthetic Fabrics vs. Organic Cotton: Impact on Skin Health

Discover how polyester and other synthetic fabrics can irritate your skin and why organic cotton, especially Pima cotton, is a healthier and safer choice for sensitive skin.

What Peru Whispers: Organic Pima Cotton Grown with Tradition and Care

In the quiet corners of Peru, organic pima cotton is grown with respect for the land. A luxurious, timeless textile waiting to be discovered.

Why Sustainable Fashion Shouldn’t Be Fast Fashion

Recycled materials and green labels won’t fix fast fashion. Discover why real sustainability means slowing down.