Circular Fashion:

The Sustainable Future of the Industry

.

AYA | JANUARY 23, 2025

READING TIME: 8 minutes

Every year, the fashion industry releases a staggering 1.2 billion tons of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere [1,2], dumps half a million tons of microplastics into our oceans [1,2], consumes 132 million tons of coal [1,3], and uses a whopping 9 billion cubic meters of water [1,3]. On top of that, it's responsible for using a quarter of the world's toxic chemicals [1,4]. These figures highlight the immense environmental burden of producing the clothes we wear. But the problem doesn't stop there. What happens to all those clothes once we're done with them?

Textile waste isn't just about old t-shirts and jeans; it includes carpets, curtains, towels, and a whole range of fabric-based products. Of the 12.6 million tons of textile waste generated globally, a shocking 41.3% comes directly from the fashion industry [5]. And here's the real kicker: according to the EU, less than 1% of all textiles worldwide are recycled into new clothes [5]. This means that out of the 5.2 million tons of clothing produced annually, a mere 52,000 tons are actually given a second life.

Years of unchecked consumerism, driven by the fast fashion industry, have led to a crisis of overproduction and waste. Mountains of discarded clothing pile up in landfills, microplastics pollute our oceans, and textile workers face exploitative conditions. In response to this growing crisis, it is time to reinforce a paradigm and make it part of our ethos: circular fashion.

Rethinking the fashion life cycle: the approach that circular fashion offers

Circular fashion challenges the traditional linear model of "take, make, dispose" [6]. Instead, it champions a closed-loop system where resources are kept in use for as long as possible, extracting maximum value before ultimately recovering and regenerating products and materials at the end of their life. This approach minimizes waste, conserves resources, and drastically reduces fashion's environmental impact. It's a model fundamentally incompatible with the unsustainable practices of fast fashion [7].

While the concept of circular fashion holds immense promise, the reality is complex. Recent data and emerging controversies highlight the challenges we face in achieving a truly circular fashion system.

Source: The Sunday Snug. "Circular Fashion Trends: Sustainability Guide." Accessed January 23, 2025.

Unraveling the Threads: Key Concepts in Circulary

Sustainable Fashion vs. Circular Fashion: Allies, Not Opposites

The UN defines sustainability as meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [8]. Sustainable fashion strives to achieve this by ensuring ethical and environmentally sound practices throughout a product's lifecycle, from raw material extraction to disposal [6].

Circular fashion, on the other hand, focuses on giving regenerative value to the linear process that currently dominates the industry [6]. It aims to transform the industry by integrating circular economy principles into every stage of the fashion cycle.

While eradicating fast fashion overnight is unrealistic, circularity offers a pathway towards greater sustainability. This transition involves encouraging fast fashion brands to adopt durable materials, eliminate disposable elements, and design versatile garments [6,9]. For conventional brands, it means implementing take-back programs for used clothing, utilizing recycled materials in new garments, and embracing secondhand clothing as a viable business model [9]

Sustainable fashion and circular fashion are not mutually exclusive; they are complementary approaches. Sustainable fashion encompasses a broader ethical and environmental perspective, while circular fashion provides a concrete framework for achieving a closed-loop system. In essence, sustainable fashion embraces circularity as a key strategy for minimizing environmental impact.

Downcycling vs. True Circularity: Closing the Loop Completely

A major challenge in the circular fashion movement is the distinction between downcycling and true circularity. Downcycling involves breaking down materials into lower-quality products, like turning old clothes into insulation or rags [10]. This process has its limitations, as the resulting products often have a shorter lifespan and eventually end up as waste.

True circularity aims higher. It focuses on maintaining the quality of materials and products for as long as possible, allowing them to be reused or recycled repeatedly without degradation [10]. This creates a truly regenerative system where resources are continuously cycled and waste is minimized.

The complexity of clothing, with its different fibres, blends and chemical treatments, is a major barrier to effective recycling [11]. This explains why currently only 1% of clothing is recycled into new garments. The recycling industry faces enormous challenges in separating and processing various textile wastes.

Building a Truly Circular Fashion System: A Collaborative Effort

While the goals of circular fashion are clear, achieving them requires a concerted effort from all stakeholders. The European Environment Information and Observation Network (Eionet) highlighted the crucial role of designers, fashion organizations, and policymakers in driving the transition to a circular fashion industry [12].

Designers need to embrace circularity principles from the initial design stage, considering durability, recyclability, and disassembly in their creations. This involves prioritizing high-quality materials, minimizing waste during production, and making it easy to separate components for recycling [5]. Key design concepts for circularity include recycling, downcycling, reconstruction, and zero-waste pattern cutting [9].

Investment in innovative textile recycling technologies is crucial to overcome the limitations of current processes and enable true circularity [5]. Currently, a significant portion of clothing collected for recycling ends up incinerated or landfilled, highlighting the need for more effective recycling solutions.

Improving manufacturing infrastructure and processes is also essential. This includes implementing water reuse systems, as the textile industry accounts for 20% of global wastewater [9]. Optimizing processes to minimize water contamination and exploring reuse alternatives for fabric scraps and discarded garments are also vital steps towards circularity.

Finally, shifting consumer behavior is crucial. Consumers need to be educated about the benefits of circular fashion and encouraged to embrace practices like buying less, choosing durable and repairable garments, and participating in clothing swaps and rental services [5]. Appealing to consumers' emotions and values can be more effective than simply focusing on technical aspects [11]. While interest in sustainability is growing, many consumers remain hesitant to adopt practices like buying secondhand or renting clothes. A 2019 Nielsen report indicated that although 66% of global consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable products, this percentage decreases when it comes to fashion, where perceptions of quality and price still dominate purchasing decisions.

The Role of Education, Policy, Business Models and behavioural change inCircular Textile Systems. Source: EEA/Eionet 2019.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

Barriers to Overcome: Navigating the Challenges

The Durability Paradox

Circular fashion emphasizes durable, long-lasting garments that can be used and reused for many years. However, this raises a potential economic challenge for the fashion industry. If people buy fewer clothes, how will the industry remain profitable?

This "durability paradox" is a complex issue with no easy answers. Some argue that a shift towards "slow fashion" could lead to job losses and economic decline. Others believe that a circular fashion system could create new economic opportunities, but it will require significant investment and innovation.

A 2023 report by McKinsey & Company suggests that a circular fashion system could generate $560 billion in annual value by 2030, creating new jobs and business models [13]. However, this will require a fundamental shift in the industry's approach to design, production, and consumption.

Greenwashing and Misleading Claims

As circular fashion gains popularity, there's a growing concern about greenwashing. Some brands are using the term "circular fashion" as a marketing tactic without implementing truly circular practices. This misleads consumers and undermines genuine efforts towards sustainability.

A 2024 survey by the Changing Markets Foundation found that many fashion brands make misleading claims about their circularity initiatives, using vague language and lacking transparency about their processes [14]. This highlights the need for greater regulation and standardization in the industry to ensure that "circular fashion" claims are credible and verifiable.

Social Justice Concerns

While circular fashion aims to reduce environmental impact, it's important to consider the social implications as well. Some critics argue that a focus on recycling could shift the burden of responsibility to developing countries, where much of the textile waste is processed.

Ensuring fair labor practices and safe working conditions throughout the circular fashion supply chain is crucial to avoid social exploitation. A 2023 report by the World Bank highlights the need for greater investment in waste management infrastructure and worker safety in developing countries to support a truly circular and equitable fashion system [15].

Changing Demographics and Preferences

The pandemic also highlighted shifting demographics in the fashion market. Younger consumers, particularly Gen Z and Millennials, became increasingly influential in shaping purchasing trends. Research from the Institute for Sustainable Fashion indicates that younger generations are more likely to support sustainable brands, with 83% of Millennials stating they prefer to buy from companies that share their values [7,8].

Moreover, with the rise of remote work, many consumers reported a preference for comfort over style. A study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management noted that comfort became the primary driver of clothing purchases for many consumers, with 65% prioritizing comfort in their buying decisions [9]. This trend is likely to persist as remote work becomes a more permanent aspect of many industries.

The Role of Community Clothing: A Catalyst for Change

Within the broader movement towards circularity, Community Clothing initiatives play a vital role. By fostering collaboration, promoting ethical practices, and empowering consumers, they can accelerate the transition to a more sustainable fashion industry.

While data on the economic and social impact of clothing swaps and donation initiatives is limited, the secondhand clothing market offers a compelling example of how community-driven solutions can contribute to circularity. In 2023, the global secondhand clothing market reached a value of US$211 billion [7]. This thriving market provides an alternative to discarding fast fashion garments and redirects them back into circulation.

Community Clothing initiatives demonstrate that it's possible to create beautiful, high-quality garments while fostering an ecosystem of exchange and generating new business opportunities based on sustainability and environmental education.

Embracing a Circular Future

Circular fashion is not merely a trend; it's an urgent necessity. The environmental and social costs of the current linear system are unsustainable. By embracing circularity, the fashion industry can create a more equitable and regenerative future.

The journey towards a truly circular fashion system will be challenging, but it's a journey we must undertake. By working together—brands, consumers, policymakers, and innovators—we can transform the fashion industry into a force for positive change. The future of fashion is circular, and it's up to all of us to make it a reality.

Glossarykeywords

Circular Fashion:

It is a clothing production and consumption model that seeks to reduce waste and pollution. It is based on economic circularity, which prioritizes the reuse and recycling of materials and products.

Closed-Loop System:

A production process where resources like water or solvents are continuously recycled and reused, minimizing waste and environmental impact.

Community Clothing:

It refers to clothing brands that adopt ethical fashion, social justice, and sustainability principles while seeking to empower and strengthen local or specific communities.

Consumer Behavior:

They are all the attitudes, preferences, intentions and decisions that govern a consumer throughout the process of buying a product or service.

Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG):

Trap heat and keep the planet warmer than it would be without it.

Microplastics:

Tiny plastic particles, smaller than 5mm, found in the environment from the breakdown of larger plastics or industrial processes.

Secondhand Clothing:

It refers to clothing and accessories that used to be owned by someone else and are now being resold rather than thrown away.

Sustainable fashion:

Clothing made using eco-friendly materials and ethical production practices.

Sustainability:

"Meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (ONU, 1987).

Zero waste:

A philosophy of minimizing waste by reusing, recycling, and reducing materials.

Glossarykeywords

Circular Fashion:

It is a clothing production and consumption model that seeks to reduce waste and pollution. It is based on economic circularity, which prioritizes the reuse and recycling of materials and products.

Closed-Loop System:

A production process where resources like water or solvents are continuously recycled and reused, minimizing waste and environmental impact.

Community Clothing:

It refers to clothing brands that adopt ethical fashion, social justice, and sustainability principles while seeking to empower and strengthen local or specific communities.

Consumer Behavior:

They are all the attitudes, preferences, intentions and decisions that govern a consumer throughout the process of buying a product or service.

Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG):

Trap heat and keep the planet warmer than it would be without it.

Microplastics:

Tiny plastic particles, smaller than 5mm, found in the environment from the breakdown of larger plastics or industrial processes.

Secondhand Clothing:

It refers to clothing and accessories that used to be owned by someone else and are now being resold rather than thrown away.

Sustainable fashion:

Clothing made using eco-friendly materials and ethical production practices.

Sustainability:

"Meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (ONU, 1987).

Zero waste:

A philosophy of minimizing waste by reusing, recycling, and reducing materials.

References:

[1] Kaczmarek, M. (2025). The Role of Social Media in Sustainable Fashion Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(1), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010502

[2] Fibre2Fashion. Sustainability: The future of fashion [Internet]. Fibre2Fashion; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.fibre2fashion.com/industry-article/7269/sustainability-the-future-of-fashion

[3] House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee. (2017). The Environmental Impact of the Fashion Industry. London: House of Commons. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/2311/231102.htm

[4] United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2023). UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion Addresses Damage of Fast Fashion [Internet]. UNEP; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.unep.org/news-andstories/press-release/un-alliance-sustainable-fashion-addresses-damage-fast-fashion

[5] Reconomy. (2024). The State of the Circular Economy in the Fashion Industry [Internet]. Reconomy; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.reconomy.com/2024/09/03/the-state-of-the-circular-economy-in-the-fashion-industry/

[6] Singh, S. (2024). Cultivating Circular Design in Fashion Education: Navigating Challenges and Fostering Sustainable Practices. NIFT Journal of Fashion, 3, 126-154. Available from: https://nift.ac.in/sites/default/files/2024-05/ejournal/volume-3/NIFT%20Journal%20of%20Fashion%20Volume-3.pdf#page=135

[7] Sheikh, M. H., & Su, J. (2024). An Empirical Study on Consumer Perceived Value of Circular Fashion. International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings, 18540. Available from: https://www.iastatedigitalpress.com/itaa/article/18540/galley/16478/view/

[8] United Nations. (1987). Our Common Future. [Internet]. United Nations; 1987 [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability#:~:text=In%201987%2C%20the%20United%20Nations,to%20meet%20their%20own%20needs.%E2%80%9D

[9] Escourido-Calvo, M., Prado-Domínguez, A. J., & Martin-Palmero, F. (2025). Generation Z, Circular Fashion, and Sustainable Marketing. International Journal of Digital Marketing, Management, and Innovation, 1(1), 1-23. doi:10.4018/IJDMMI.367035

[10] Interfaith Sustain. (2023). Downcycling [Internet]. Interfaith Sustain; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://interfaithsustain.com/downcycling/

[11] Wagner, M. M., & Heinzel, T. (2020). Human Perceptions of Recycled Textiles and Circular Fashion: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 12(24), 10599. doi:10.3390/su122410599

[12] Ahn, H. J. (2021). Circular Fashion: A New Paradigm for Sustainable Fashion. Journal of Fashion Design, 31(2), 213-225. doi:10.1080/14606925.2021.1936748

[13] Amed, I., Balchandani, A., Barrelet, D., Berg, A., D’Auria, G., Rölkens, F., ... & Woetzel, J. R. The State of Fashion 2020. New York: McKinsey & Company; 2020.

[14] Changing Markets. (2023). Synthetics Anonymous: Fashion Brands' Addiction to Fossil Fuels [Internet]. Changing Markets; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://changingmarkets.org/report/synthetics-anonymous-fashion-brands-addiction-to-fossil-fuels/

[15] World Bank. (2022). The State of Fashion 2022 [Internet]. World Bank; 2022 [cited 2025 Jan 22]. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099429103052453052/pdf/IDU11a1ba0d91eff114fe218a7f133880865e386.pdf

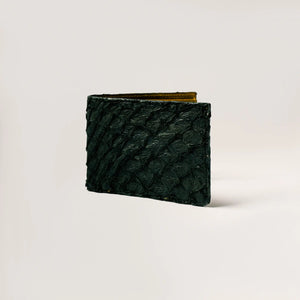

You don't have to put all the weight on your shoulders. Every action counts. At AYA, we fight microplastic pollution by making a 100% plastic-free catalog.

Visit Our Shop →You May Also Like to Read...

Earth Day 2025: Uniting Climate Action & Sustainable Fashion

Explore Earth Day 2025’s urgent call to combat climate change, fast fashion, and the role of sustainable innovation which is slowly making a real difference.

The Battle for Mangroves and Ponds in a Changing World

In this article, we critically examine the innovations and policies emerging to conserve mangroves and ponds, an urgent and decisive need for global coordination.

Guardians of Life: The Hidden Power and Crisis of Tropical Forests

In the context of Earth Month, this article critically examines the benefits of tropical forests, the dual-edged impact of industries such as fashion and petroleum extraction.

Zero Waste Day: The Urgent Fight

In the framework of Zero Waste Day, this article will critically examine the multifaceted waste footprint of fashion, highlighting the urgent need for systemic change.